Remembrance of Things Past

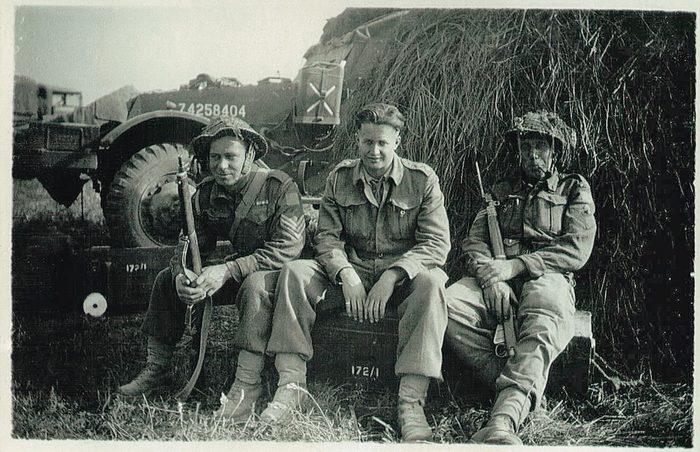

I keep the old black-and-white photo on my desk for a reason. I have a number of pictures of my father but I chose this one because whenever I look at it, I think about so many things. My dad, Lt. John Horsburgh, is in the centre of the photo; on the left is Sgt. Clifford Hebner and on the right is CSM Cormack. Studying the photo, I wonder why the jeep is partially hidden in the haystack or why Sgt. Hebner has a dent in his helmet? I also notice how CSM Cormack appears to be sleeping with a pipe in his mouth while holding a rifle with a bayonet at the end of it. Most of all though, I wonder what these three individuals are thinking about. To me the picture conveys so much more than simply portraying my dad and two Royal Canadian engineering corp comrades sitting on a trunk behind a haystack.

Taken in early August 1944, the image shows them in relaxed poses that I sense must belie what they had just been through: D-Day with its horrendous death toll, destruction and utter chaos; the breakout from Juno Beach with the fierce fighting, unimaginable bombing and shelling; and examples of bravery and evil that showcased the best and worst of war. On the back of the picture my dad wrote: “The day after the start of the big push for Falaise.”

Earlier in July, Clifford Hebner had won the Military Medal for outstanding leadership under fire south of Caen. Caen was also the location where my father won the Military Cross on July 18, 1944, as a result of his actions in conducting a thorough reconnaissance of the River Orne while under fire from the Germans. The reconnaissance facilitated the building of a bridge, which enabled more than 100 tanks to cross the Orne in the next 24 hours en route to Falaise.

On the back of the picture, written in brackets beside Sgt. Hebner’s name, is “since killed.” While my dad lived to see the end of the war, Sgt. Hebner died less than two months after this picture was taken. Tragically, he was killed in Belgium on October 5, 1944, while trying to defuse a German land mine. He is buried in a cemetery near Antwerp, Belgium. He was only 32 years old and was married, but as far as I can determine, he did not have any children.

I couldn’t help but want to know more about Sgt. Hebner. If I was able to locate a member or members of his family, I figured they might appreciate having a copy of this photo. I wondered if anyone from Sgt. Hebner’s family has had the opportunity to honour his sacrifice by visiting his grave in Belgium?

As I thought about the picture some more, I also wondered how Sgt Hebner’s death affected my dad. I suspect that military censorship was such that my dad was limited in what he could say about his comrade’s death. I am sure the words “since killed” did not even begin to convey the sense of loss and sadness my father must have felt when he gazed at this picture and wrote his comments on the back.

Sadly, while my father dodged death in northwest Europe, he was killed seven years later in a float plane crash while serving his province as the senior hydraulics engineer in 1952.

Sgt. Hebner, my father and CSM Cormack were examples of men who lived Albert Schweitzer’s dictum that “you who will be truly happy are those who will have sought for and found a way to serve.”

This picture makes me think about the concept of service, about how important it is to have a belief in this simple yet profound concept and that through service, we can make a difference in the lives of others. There is no doubt this photo speaks to me in a very personal and profound way.

I decided to undertake a search for information about Sgt. Hebner and CSM Cormack. After months of getting nowhere, someone finally responded positively to one of my inquiries. The response came from a most unlikely source.

My wife and I attended a Winnipeg Fringe Festival play entitled Jake’s Gift. It’s a heartwarming, award-winning play about a World War II veteran who travels back to Juno Beach to visit the gravesite of his older brother. It turns out that the name of the brother buried at Juno Beach is Chester Hebner. On the off-chance there was some connection between this name and the Clifford Hebner I had been searching for, I sent an email to the play’s website, including the picture of my father and his two comrades.

I immediately got a response from Julia Mackey who wrote and plays all the characters in Jake’s Gift. Julia emailed me back, stating that she had written the play as a result of seeing Chester Hebner’s gravesite at Juno Beach.

Julia had the information about the Hebner family I sought. We arranged to meet Julia and her husband Dirk for lunch, where Julia showed me another picture of Clifford and his friend CSM Cormack taken during World War II. Most important to me, however, she showed me a photo of Clifford’s younger sister and her husband visiting Clifford’s gravesite in Belgium.

At its core, Jake’s Gift is a paly about the importance of remembering. I had been looking at picture taken almost 70 years ago, some four years before I was born, wanting to know and understand this picture on a deeper level. What a gift it was to meet Julia and Dirk, who were able to bring this very meaningful and unique picture to life.

Remembering has to do with the past; it involves thinking about people and events that were important to us. I also believe, however, that the importance of remembering has to do with the future in terms of how it shapes our lives, clarifies our values and fundamentally helps us determine who were are and who we want to be as we move forward in life.

I am very thankful for a photo, a play and two individuals, Julia and Dirk, who have helped me to remember.