Honour & Valour

My 98-year-old father, Nicholas (Nick) Turchyniak, is sipping a happy-hour brandy and enjoying a piece of kielbasa sausage. He has a faraway look when I ask him about the war, which ended more than 70 years ago.

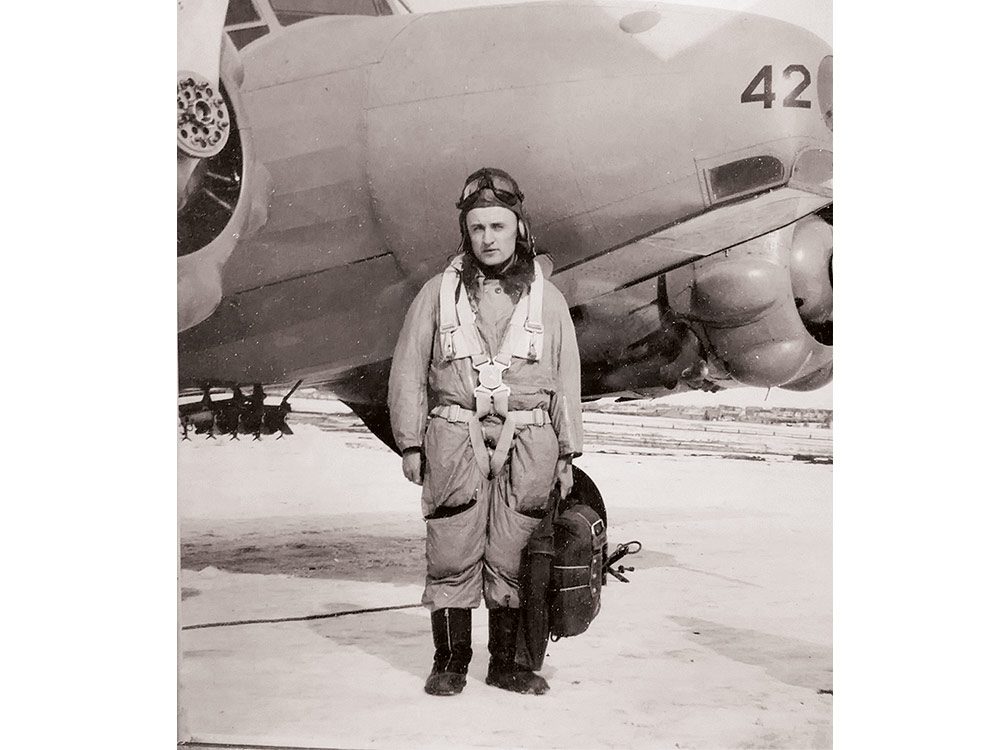

Reminiscing, he shares his past. He was born on September 3, 1920, near Prud’homme, Saskatchewan, and was one of eight children. His father, John Turczniak, came to Canada from Poland in 1905 at 15 years of age. Nick’s mother, Josephine Swidzinski, was born in 1903 in Saskatchewan. The family did mixed farming including raising cattle, horses, chickens and pigs, and provided wheat for the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool.

World War II broke out and, in 1941, Nick volunteered to join the Royal Canadian Air Force just before he turned 21. He trained in Brandon, Manitoba, as a pilot then as a navigator and was assigned to Dafoe, Saskatchewan. He eventually joined the ground school in Toronto in the armament section.

Throughout the war, Nick found himself stationed across Europe, including England, France, Holland and Belgium.

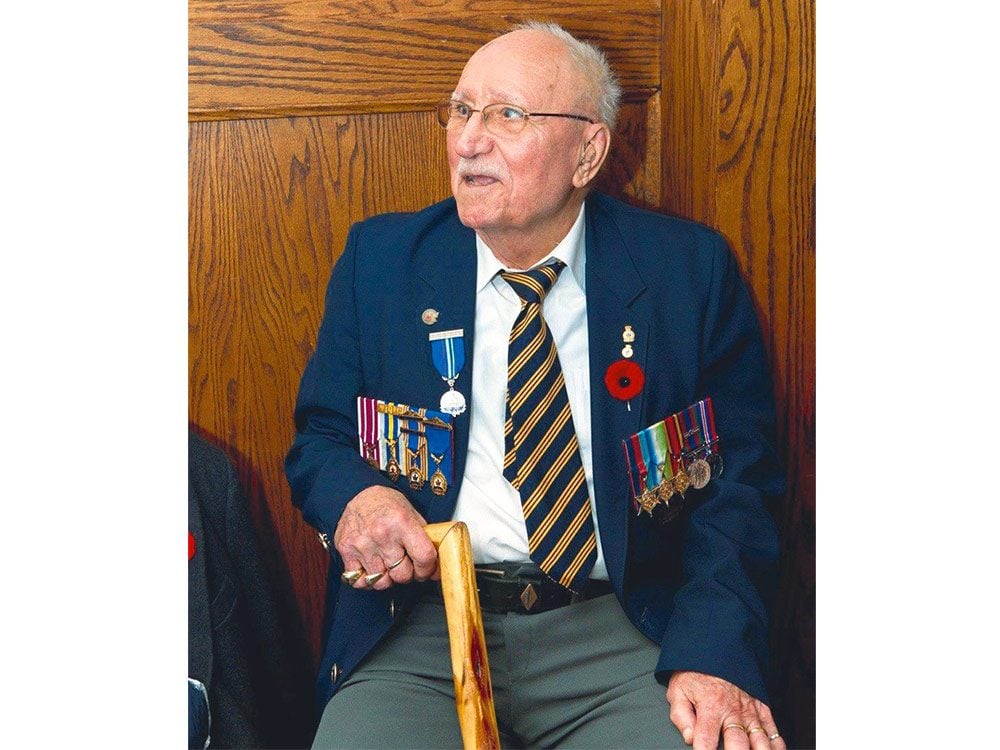

In France, he dug trenches, putting logs over top of them as German troops flew over. He also helped ground troops load their anti-aircraft guns. The Germans attacked fields and aircraft, so Nick was close to the action! Nick remained overseas in Europe until VE (Victory-Europe) Day in June 1945. He earned five war medals including the Defence Medal, the France and Germany Star, and the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal, for his war service involvement. —Gloria Lauris, Ottawa

Serving Her Country

I was born in Toronto, but grew up in Hamilton and lived there until October 1942.

Because the war had been going on for three years and I had heard that the government was running short of eligible men to fight the war, I felt it needed my help, so I joined the Canadian Women’s Army Corps as a stenographer.

I completed a one-month course in army military procedure and was then sent to Kitchener for basic training. When basic training was over, I was transferred to Trinity Barracks in Toronto for a couple of weeks. Three others and I were, for over a year, posted to the Brampton Canadian Army Basic Training Centre for men, later called the Canadian Armoured Corps Basic Training Centre, and there were hundreds of men there coming and going. One other girl and I were put in charge of the recording of anything that took place in camp, and with each soldier personally, to be entered on his records. In 1943, I was sent to army camp in Brockville for a month for an army officer’s course. When this camp closed in 1944, we were all posted out, and I arrived at Military District #2, Stanley Barracks (CWAC) at Exhibition Place in Toronto, in a fenced-in compound for 13 months. In early 1945, my commanding officer asked if I would like to go to St. Anne’s near Montreal for officer’s training or drop two stripes as corporal and go overseas. Of course, I chose overseas, which my commanding officer expected and had already started the procedure for.

In May 1945, I was posted to the Canadian Military Headquarters (CMHQ) in London, England, for a year. I was on a troop ship in convoy when, halfway across the Atlantic Ocean, peace was declared, but that ship carried on to England because the men on board had yet to be placed. I have been surprised that, to this day, I have not yet met anyone who was also on that ship.

After disembarking, I carried on to the Canadian Military Headquarters in Trafalgar Square in London and started my job there as secretary to a captain who issued the orders to send the Canadian war brides to Canada after the men had been sent home.

Incidentally, I was rewarded with my corporal stripes after a few weeks and a third stripe (sergeant) later.

By June 1946, most of the troops and their war brides had been sent to Canada, so my work was done. I was in the second-to-last group to be returned to Halifax, via the ship SS Île de France; then, I travelled by train to Toronto and by army truck to Hamilton. In July 1946, I was discharged but, for me, October 1942 to July 1946, was a good four years. —Norma Mowat, Selkirk, Ontario

Here are more incredible women you didn’t learn about in history class.

Decorated for His Service

My father, Harry T. H. Stewart (QR2), was born in Fort William, Ontario, on January 23, 1925. He joined the HMCS Griffin in Port Arthur, Ontario, in 1940 after lying about his age. His basic training was done in Port Arthur and Esquimalt, B.C. He served on merchant navy ships as a gunner aboard the Lafontaine Park and the Gatineau Park. He sailed the high seas in 1941 and saw action in the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean. Harry was in Liverpool, England, carrying supplies when the war ended. He returned to Canada in 1945 and was discharged from the navy in 1946.

He received both the Burma Star and the Atlantic Star for his service. —Penny Brown, Prince George, B.C.

A Canadian Soldier in France

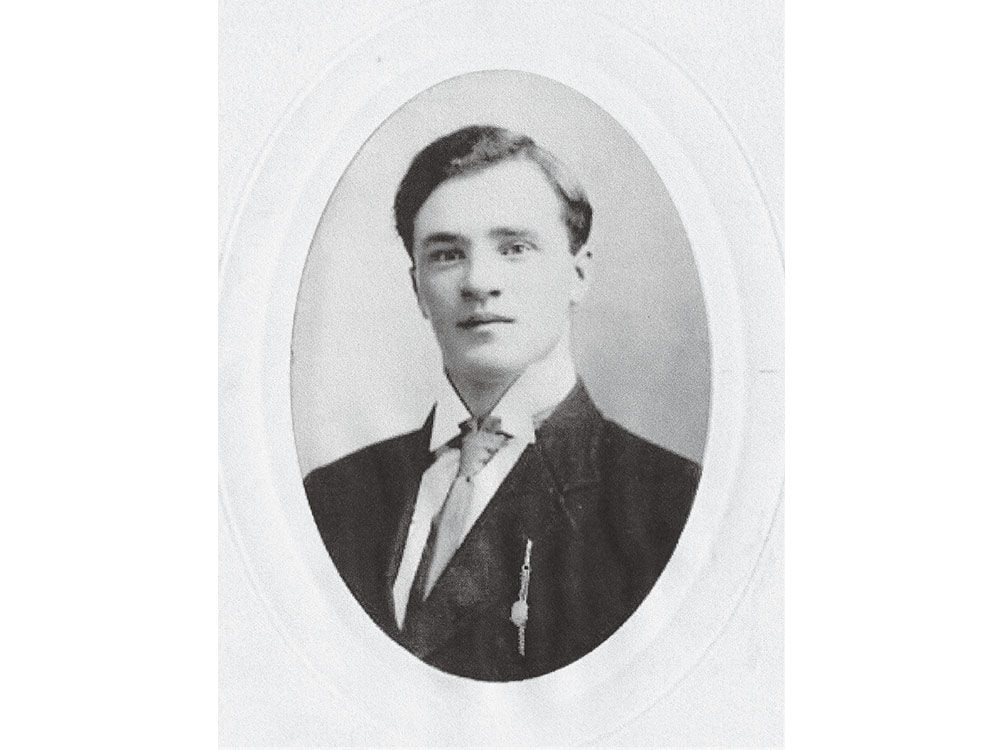

My mother’s uncle, Thomas (Tod) Victor Rutherford, was born in Ridgeway, Manitoba, on February 4, 1892, and grew up in Stonewall, Manitoba. He enlisted with the Seaforth Highlanders on September 17, 1915, serving with the 72nd Battalion. He left for Bramshott, England, in May 1916 and for France in August 1916, fighting in the trenches near and around Kemmel.

He wrote home to his mother in September of 1916: “I think we have the upper hand…our artillery has theirs eating mud all the way. Our divisional reserve hut is about 5 miles behind trenches. We are here 4 days and out 16 (i.e. 4 days here, 4 days in trenches, 4 days at Kemmel, 4 days in trenches). The food is fare and we are treated well. The trenches are in bad shape but we are trying to fix them up.”

In January 1917 he wrote home: “…and within six months will likely be here wounded or ‘pushing up daisies in France’ but I hope I’ll get right through it all.”

On the morning of April 9, 1917, the troops rose early and went into the Assembly trenches. After the main ridge was taken, Tod was hit by shrapnel in his left leg, but did not say anything to the other men and refused to be taken out until reinforcements were set up. By that time, it was too late.

His initial grave was marked by a small wooden cross and, as is the case with many of the graves, there were two other soldiers buried in the same plot. Later, a tombstone was erected with his name and an epitaph that reads: “He hath done what he could.” —Carol Tucker, Sandford, Ontario

Here’s the true story behind John McCrae’s “In Flanders Fields.”

Two-Time War Vet

My grandfather, Richard I. Clarke, was born in England in 1889. Upon immigrating to Canada, he joined the army in 1916, serving with the 38th Battalion, 4th Division. On Easter Monday, April 9, 1917, as he was advancing upon the German trenches at Vimy Ridge, he was knocked senseless by a shell. The shrapnel tore through his shoulder and he was sent back to England.

There he married Elsie Nellie Woodward Keene and returned home to Toronto with his war bride after the war ended.

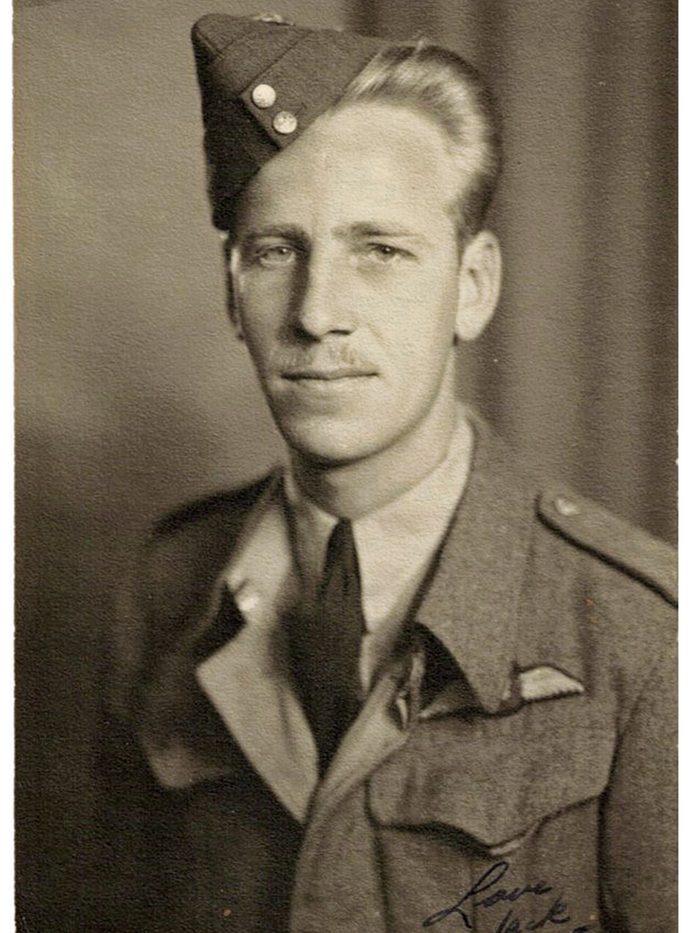

They had four children. In 1939, their son Jack Clarke joined the navy and was sent out to sea on the battleship HMS Duke of York. Richard also volunteered as acting sergeant in the 27th Veteran’s Guard, I Wing, to guard German prisoners in Alberta. He returned with a German-carved wooden novelty box, which I still have. Jack returned with a war bride. Richard lived to be 86, passing away in 1975, while Elsie passed away the previous year. —Doug McBeth, Ottawa

Haunting Memories

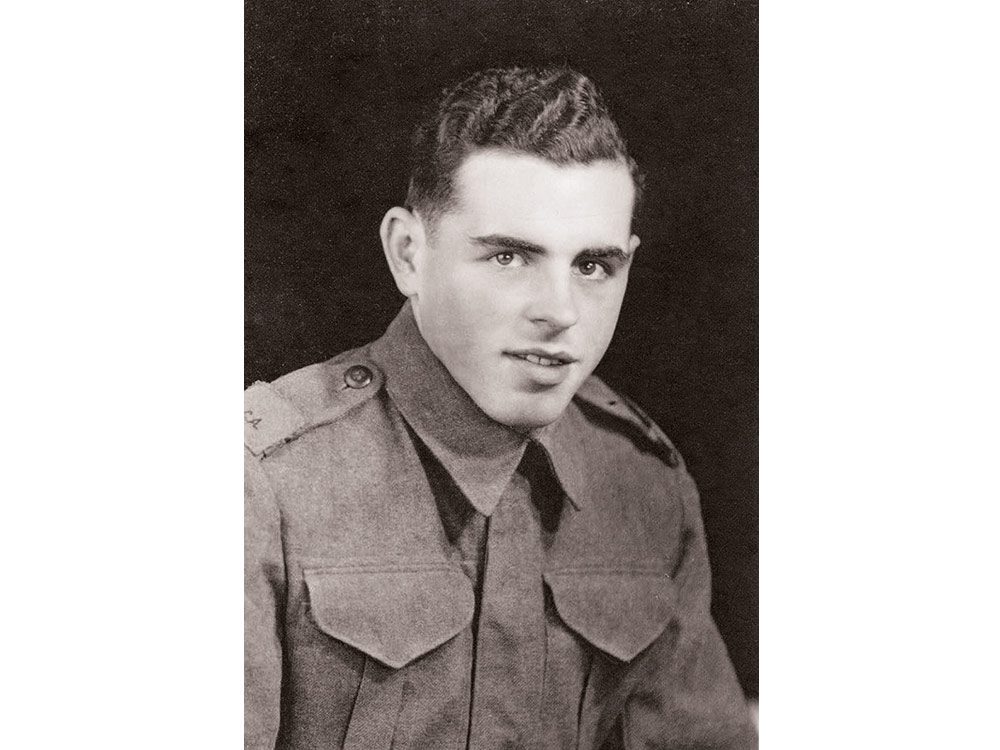

Now 99 years old, my great-uncle Joseph Émilien “Marcel” Boucher was born on February 29, 1920, in St-Adolphe de Dudswell, Quebec. At 17, he enlisted with the Canadian army in Cowansville, Quebec. He did his basic training in St-Jean d’Iberville and later trained as a gunner and a signalman as well as paratrooper with the RCA. (Royal Canadian Artillery) in Petawawa Ontario, with the 2nd Medium Royal Canadian Artillery Regiment.

In 1942, he left for Halifax by train from Petawawa when they were ordered to go overseas. Due to illness, he could not leave with his regiment, so he left later with the 4th Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (formed of only French Canadians). Marcel stayed with this regiment, which became his family till the end of the war. He landed in Normandy on July 9, 1944, and continued to fight until May 10, 1945.

He was part of the attack of Falaise to try to close the Falaise gap, which trapped close to 50,000 German enemies inside this gap. He remembers Faubourg de Vaucelles and Carpiquet, Passchendaele, Gand and particularly Nijmegen.

As the world celebrated the end of war, he and other soldiers in his regiment could not join in the festivities—they had to remain on duty to protect the border in case some Germans tried to cross or retaliate. When he was 89 years young, he did a video interview about his war efforts; never had he mentioned or talked of the war before that time. His visual memories still haunt him, and certain smells continue to trigger memories—both good and bad. —Marie-Josee Boucher, Hearst, Ontario

Read about how this organization is helping veterans tell their stories.

Still Going Strong

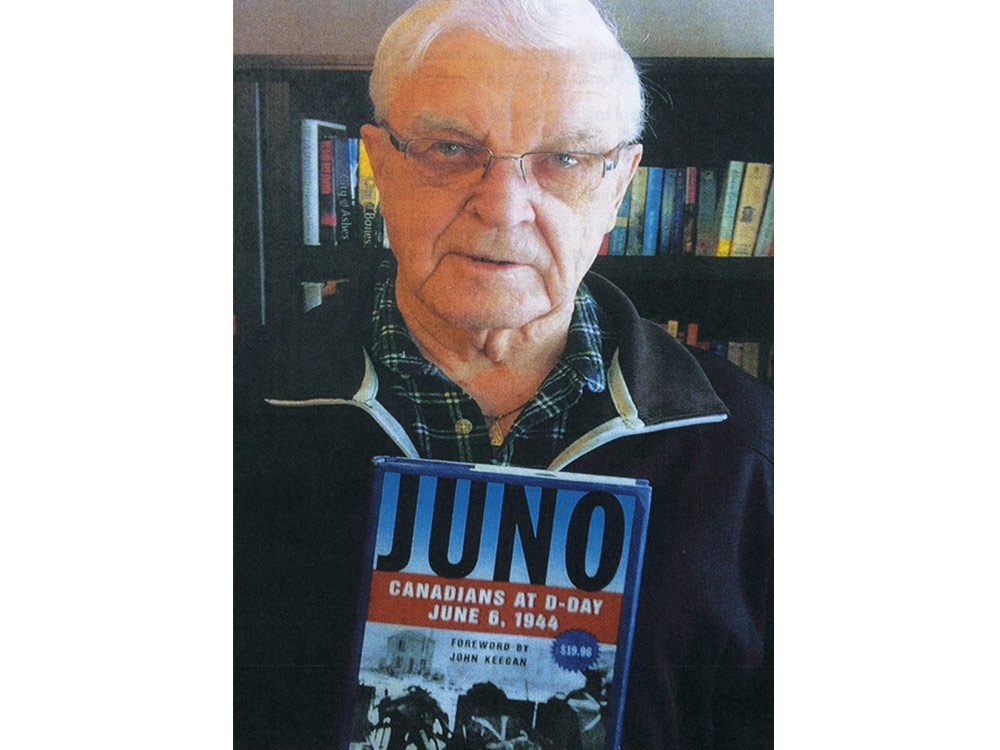

My dear friend and World War II veteran, John Kuharski is a very active 99-year-old gentleman residing here in Kamloops, B.C. John was born near Eden, Manitoba, on August 26, 1920. He enlisted with the 10th Armoured Regiment, Fort Garry Horse in Winnipeg on June 17, 1940, and trained at Camp Borden, Ontario.

He was shipped to England and was stationed at various locations in preparation for D-Day.

John says, “On June, 6, the order was given to move out. Ships, planes, troop carriers, everything and everybody were on the move. We landed at 7:20 a.m., after Juno Beach was cleared to some extent. The bombing was happening on shore and all around. It was an eye-opener. I was driving a Sherman tank.”

After the tank received battle damage, John drove a fuel truck for the remainder of the war as the Canadians advanced north through Europe. The war ended when they were in Oldenburg.

Following the war, Lance Corporal John Kuharski returned to his wife and family and was discharged on September 7, 1945, in Winnipeg. John now resides in Kamloops. —Ted Kowalsky, Kamloops, B.C.

Life-long Devotion to Service

I was born in Arnprior, Ontario, in 1925. Joining the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC) in 1944, I did my basic training in Kitchener. I was posted to the Glebe barracks in Ottawa and worked in the casualty department in temporary buildings at Preston and Carling St. In 1946, I was discharged as a corporal when the CWAC was disbanded. I married a soldier named Edward and for the next 25 years we lived on army bases in military housing in Camp Borden in Ontario, as well as Whitehorse, Winnipeg and Kingston, Ontario. Edward passed away in 1994 and I remained in Kingston till four years ago, when I moved here to Port Elgin, where two of my sons reside. —Alice (Wright) Winter, Port Elgin, Ontario

Read the incredible story of Fern Blodgett Sunde, Canada’s first female wireless operator to serve on a warship.

A Dashing Figure

My friend Tom E. Vance was born on July 26, 1922, in Ottawa. Leaving high school after Grade 10, he began driving a truck for his dad’s store and eventually began a trucking venture of his own. The news of war was everywhere and Tom decided to join up. Wanting to join the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) but needing more education, he completed a special course in Hamilton and signed up with the RCAF in March, 1942. After completing flight training in Goderich and Aylmer, Ontario, he went to England for advanced flight training. Tom joined the 411 Spitfire Squadron in Holland and saw a lot of action in the final months of the war. Returning home, he eventually opened his own clothing store. At 98, Tom is still an active member of the RCAF Association. Since the passing of his wife Edna (his teenage sweetheart), he resides in a retirement home here in Port Colborne, where he enjoys life near his daughter. —Norman Sonnenberg, Port Colborne, Ontario

Letters From the Front

“When an air raid occurs, you’ve got to tumble off your bed (three planks of wood), grab your steel helmet and spend hours in the dug-out until the fun is over. Sometimes, it lasts about two hours, so it’s no joke. But it’s an amazing sight, watching the searchlights probing the skies, hearing the drone of the planes, the terrific burst of the anti-aircraft guns, and the still noisier bombs from the ‘Jerry’ planes.”

Every Remembrance Day during the two minutes of silence, while the haunting strains of the “Last Post” play, I visualize my uncle, Norman Parker, manning anti-aircraft guns in the Western Desert Campaign in North Africa during World War II.

My impressions come from a small bundle of letters from relatives and friends of my parents that I found among my late mother’s possessions. The letters bear three-penny postage stamps and an indelible blue ink rubber stamp reading, “Passed By Censor.”

I believe my mother kept these particular samples as they offer congratulations on my birth on November 4, 1941:

“I’m very glad to hear about the new arrival in the family. It certainly is a very nice name you have chosen for her. I am looking forward to seeing her very much, and I hope it will not be very long before I am back,” wrote Uncle Norman.

These letters offer a sanitized glimpse of a soldier’s life at the front. The idea was to retain confidentiality and to downplay the terrors of the war to shield loved ones at home.

The first letter from the pile is dated October 2, 1941, and reads:

“A line or two from Egypt. I’ve been here for about two months now. And though I’ve searched about for what novelists often describe as ‘that lure of the desert’ or ‘the romance of the desert,’ I’ve found nothing but sand, sand and more sand.”

Another letter offers the following description:

“The only place that I have found with a bit of colour is where we are camped at now. It is really quite pretty here, as there are masses of all sorts of wildflowers, the prettiest of which are real poppies, and they are blood red, and certainly a sight for sore eyes in the desert.”

Other letters refer to the living conditions:

“We’ve been having intermittent sandstorms; the sand, which is fine and powdery, is whipped up by the wind, accompanied by a whining noise, and you can’t see three feet ahead. Everything becomes covered by desert, your food, blankets, etc. But you get used to it.”

The letters also mention the names of battles that took place in the Western Desert Campaign including Bardia, Sollum, Halfaya and Sidi Rezegh, without going into any details except to add:

“We had a good share of the action,“ or “We were on the run, and inevitably, “We didn’t get much sleep or a decent wash.”

One letter gives an account of an air raid:

“Once I saw a plane caught in the searchlight, as a resort to getting out, dive right down the beam, and the bullets from its machine guns going right down into the light. When the shells or bombs come your way, they whistle.”

From the sketches in the letters, days off offered a sense of relief. “A decent meal, bath and show, and believe me, one needs it here.”

Leave comprised visits to places such as Cairo and Alexandria.

“I have been very fortunate in being able to see quite a fair bit of the cities in this country as I was stationed outside Cairo for just over a month. I have been out to see the Pyramids and the Sphinx and to most of the mosques, and it was really very interesting. Cairo has a huge population.”

Another account gave his impressions of Alexandria:

“Alexandria is a blending of the new with the old, the East with the West. It’s an oriental city, white buildings, square-topped, dust, heat and thousands of uniforms. I never want to see another uniform after this war.“

Norman was spared and returned home safely to become an enormous influence on my life. As a young child, he was my fairy godfather showering me with treats or a coveted half crown on each visit.

As a teen, he became my mentor, encouraging me to study hard and rewarding me with a camera on completing high school. On my wedding day, he drove me to the church and said, “You make a beautiful bride.” He delivered the toast to the bride and groom, ending with a line from “Ode to the West Wind” by Percy Bysshe Shelley: “If winter comes can spring be far behind?”

Considering the difficulties he overcame fighting in World War II, I didn’t anticipate anything as challenging ahead of me.

He was my role model my entire life. He was highly principled, fiercely patriotic and believed in doing his duty, which made him a hero in my eyes. He was not only a perfect gentleman but also a gentle man. I can’t imagine what my life would have been without his guidance and nurturing.

Each Remembrance Day, as I fondly recall all he did for his country and me, I am overcome with melancholy as I despair at all the lost lives and empty places in other families. We can never forget the sacrifices of these men. —Penny Heneke, Burlington, Ontario

This letter from a Canadian soldier explains the sacrifice of veterans everywhere.

Fly Away Home

My dad, Charlie Patterson, was born in 1919 and enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1940 at the age of 21. He was sent to Galt Aircraft School for training and graduated in 1942. He was shipped to England, where he was stationed at Topcliffe, Yorkshire. Assigned to the Dunlop Rubber Co., he was a very good mechanic and worked on many bomber aircraft, including Lancasters and Spitfires. He returned home in 1945. I’m so proud to be the daughter of a veteran. —Rose Cole, Cambridge, Ontario

Here’s how Canada helped recover one of WWII’s most iconic aircraft.

A Well-Deserved Honour

Born July 2, 1939, and hoping to escape a working class future, I enlisted in the army at age 18. Not yet understanding the army philosophy of “never volunteer,” I volunteered for everything, including advanced combat training and an overseas posting. Within a year, I was posted to Singapore and saw combat in the jungles of Malaya, during the Malayan Emergency and once in Borneo, at the start of the Borneo Confrontation. I was later posted to South China and based in Kowloon and Hong Kong with tours of duty in the New Territories for patrolling the Chinese border. For those tours of duty, I proudly wear the General Service Medal (GSM Malaya), General Service Medal (GSM Borneo), and the South Asia Service Medal (SASM).

Following completion of the seven-year active commitment, and relocation, I joined the Canadian Armed Forces Reserve, where I served until the age of 60. During my service with the Canadian Armed Forces, I received a Queen’s Commission, and on completion of my service held the rank of captain, in training systems command. For my service with the Canadian Armed Forces, I received the Canadian Decoration (CD) and later the rosette addition.

While proud of previous military awards, I was even more proud, and surprised, when, 50 years after the event, and living a quiet retired life in Keswick, Ontario, I received a phone call from the Malaysian consulate. I was advised that the current King of Malaysia had ordered a special medal to be cast to show his country’s deep appreciation for the service and deeds performed by certain foreign military personnel, which resulted in Malaysia’s independence. My name appeared on that list. A few days later, a small leather box arrived containing the Pingat Jasa Malaysia (PJM) medal from Malaysia, a small brass plaque and a letter of gratitude for services rendered.

I now live in the retirement community of Elliot Lake, Ont., with my memories from a life of service to my country. —Reg Couldridge, Elliot Lake, Ontario

The Singing Cowboy

Ninety-six years ago was born a man of very high standing in the eyes of many, especially mine. My father, Edgar Chevrier, was born in Rourget, Ontario, on May 1, 1924. At the age of 18, he joined the Algonquin Regiment of the Canadian Army where he became a sergeant, and eventually a master sergeant.

During the war, he was stationed in Holland, France and Germany. He never talked much about the war—four years is a long time to spend in a dark place. When he wrote home, though, there was never a word of discouragement, only cheerfulness. As well as serving in the army, Dad was also an entertainer in the Canadian Army Show. He performed in a band called the Arkansas Travellers and played guitar. He entertained at many events and his younger brother Bert accompanied him. A much-requested song was “The Little Shirt My Mother Made for Me,” which their younger sister Aileen would dance to.

Sadly, during this period of time, his younger brother Bert was killed in action.

After the war, Dad became a heavy duty diesel mechanic and worked at Algoma Steel in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. He loved sports and was involved in hockey as a trainer for the Soo Falls Dorans juvenile hockey team and was an assistant coach for the Soo Canadians. He also played softball.

He continued to entertain, singing and playing with Don Ramsay’s Ramblers. He was also known as “Algoma’s Singing Cowboy.”

Dad passed away in 1971 at the age of 47. —Gloria Aikens, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario

Read the moving story of how, after 70 years, this Canadian soldier was finally laid to rest.

Winds of War

War was imminent when Ken Foote (my dad) was finishing high school in West Vancouver in 1939, so instead of carving out a civilian career for himself, he decided to join the army. After basic training, he was posted to Yorke Island, up the west coast of British Columbia, at the entrance to Johnstone Strait, where a gun emplacement and fort were being set up as part of the West Coast defences. Endurance, military skills and resourcefulness were learned there, and close friendships formed. Eventually, Ken was sent to Esquimalt, B.C., where he took the officers’ training course, and was then posted to Vancouver, where he was involved with radio operations. While there, he met Mary Wood (my mom), a Saskatchewan farm girl who had joined the Canadian Women’s Army Corps. They got engaged in December 1943.

The British Army was in dire need of replacements, and so Ken and a number of others were slated to go there. First, he was sent to Shilo, Manitoba, for more artillery training.

Sweethearts Ken and Mary were wed in June 1944, and in August he was posted to the front via England. Ken also served in France and Belgium, before being sent to Arnheim, Holland, where the noted offensive was in progress.

His group was stationed in a church cemetery of all places and, during skirmishes one day, Ken was edging around the corner of the church at the same time as a German soldier came around the next corner. In the exchange of gunfire that ensued, Ken was hit in the abdomen by two bullets, one exiting near his spine. The outlook was grim, but an army doctor operated on him in the church basement, removing the remaining bullet and stabilizing him enough so that he could be transferred back to England for further medical procedures. He was eventually evacuated home on a hospital ship.

After his recovery, Ken and Mary made their home in Kamloops, B.C., where he worked at the local radio station. Eventually, he and Mary settled back on the coast, where Ken careered with the UIC (now part of Service Canada). They adopted six children over the course of 13 years.

Ken served in the reserve army for some time after the war, along with many fine veterans who were also good friends. Upon retirement, he and Mary enjoyed travelling, which included a trip back to Holland and the areas where Ken had seen action.

Ken passed away in 1996 and Mary, in 2007. They are really missed by our family.

Remembrance Day is almost here once again, a time to remember those who sacrificed so much for the freedom we enjoy today. Many never came back, and those who did are becoming fewer each year—they all are truly special people. We must never forget. —Jean Humphreys, Kamloops, B.C.

Here are the the best military movies to watch on Remembrance Day.

Eternal Thanks

My uncle, George Clifford Armstrong, was born in Denzil, Saskatchewan, in 1914. He enlisted in January 1942 and saw active duty in France, Germany, Belgium and Holland as a signalman. He returned home in 1945.

In 1980, he was one of the many soldiers who received tulip bulbs and a lovely thank you letter from a family in Holland for his part in the liberation of the Netherlands. George was active in the Vancouver Legion until his death in 2002. —Lucille Chisholm, Delta, B.C.

Read the fascinating story of Canada’s oldest surviving warship.

Treasured Mementoes

This is what I recall most about the days preceding Remembrance Day when I was a child at home: My dad, Joseph Koenig, would always bring out a little blue suitcase, which contained a box of mementoes from his time in the army during World War II. He’d also bring out his medals, which were displayed in the glass front of a handmade wooden box. After bringing out his medals, he’d begin polishing them. When I got older, I was allowed to help him. He would make sure they were pinned nice and straight on his Legion uniform. This was done with lots of help from my mom, who would wear her Ladies’ Auxiliary uniform for Remembrance Day.

It wasn’t until Dad moved into a long-term care home that we found out exactly what else was kept in his special box. It also contained a large envelope with all the postcards he’d sent home to Mom, and to each of my brothers and sisters—what a keepsake! Reading those cards brought a tear to my eye. The box also contained a bracelet, scarves and all of his shoulder patches. Also enclosed were a Canadian Army training pamphlet, a schedule for the military bus service, a soldier’s guide to Sicily as well as a soldier’s service pay book.

I wasn’t born until 1949, so I didn’t experience the war, but as an adult, I’ve had time to think about what it must have been like for my mom as well as my dad. It had to be difficult for Dad to head overseas to fight for his country, leaving his wife and three kids at home to fend for themselves. I can’t even fathom what it was like to spend five years away from home.

It had to be tough on Mom, too, being left to raise the kids at home—she must have wondered sometimes if Dad would make it back. I bet Dad had the very same thoughts in the back of his mind.

We owe a debt of gratitude to all those who made the sacrifice to give us freedom—as well as to the wives and children who stayed at home, trying to make ends meet. I am so proud of my Dad and Mom.

On Remembrance Day, when we thank veterans for their service, we should also spare a thought for those who remained behind. —Frank Koenig, Morinville, Alberta

Here’s the incredible story of Ontario’s Farmerettes—Canada’s forgotten wartime heroes.

Double Duty

My father, Stanley A. Solomon, joined the army in September 1914. He fought at Vimy Ridge and the Second Battle of Ypres during WWI, as well as the Battle of the Bulge during WWII.

Trying to ask my father questions about his war years was very difficult, as he would get quite upset and walk away with tears in his eyes. Although we never learned very much about his experiences, he did tell us about being in the trenches, and how he and his fellow soldiers would wait for darkness then crawl into a nearby farmer’s field to suck the juice from frozen turnips to quench their thirst. He also told us that during battle, whenever they’d storm a hill, the first and third soldiers over the top were usually killed; I assumed that the second and fourth men survived because the enemy had to reload their guns.

After he came home from WWI, Dad married my mom and bought a small farm in the Fraser Valley, B.C., where they raised five children—far from easy during the Depression. Finding it difficult to get work, Dad enlisted again and was stationed in Alberta until 1942, the year my mother died. After his WWII service overseas, he was stationed in Vancouver until the end of the war. He then went to live in Penticton, B.C., where he worked in the armoury until it was closed down. Dad died at the age of 82. At 90 years old, I am his only surviving child. I am so grateful that he was one of the few who came home from both wars. —Lily P. Gisborne, Lady Smith, B.C.

Call of Duty

I was born in St. Catharines, Ontario, on July 5, 1925. My dad was a World War I veteran but didn’t speak much about the war except when attending reunions.

I remember the day that the Second World War was declared. I had been at the local swimming pool, and on the way home, the newspaper boy around the corner was hollering, “Extra! Extra!”—the war was on.

I decided to join the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS) and remember well the first day of training and receiving my uniform: blue dress, navy blue sweater and cap.

I also remember marching in the parade square—I was behind a girl who didn’t know her left from her right and at times marched with both arms out! But we all did our best to keep in marching formation.

As a member of the WRCNS, I was trained as a switchboard operator, taking external calls and directing them to the proper naval offices.

I served at several Navy Reserve Divisions. I first went to HMCS Star in Hamilton and then to HMCS Conestoga near Galt, Ontario (now part of Cambridge), for training. I was then sent to HMCS Peregrine in Halifax and after that to HMCS Discovery in Vancouver for a six-month stay. After that, I was granted leave, but soon enough was on the move again, this time to Montreal for a five-month deployment. I was then sent to Shelburne, Nova Scotia, and finally to HMCS Stadacona in Halifax.

Even though we were literally helping to keep the lines of communication open, we didn’t hear much about what was actually happening overseas because, as they said, “Loose lips sink ships.”

We were all so glad when the war ended. I was sent back to HMCS Peregrine and from there was discharged in 1946.

I think what we did was pretty important—all the services performed important jobs in the war effort. —Helen Betsy Mitchinson, Chatham, Ontario

Find out about the remote facility on Lake Ontario that was home to Canada’s top-secret spy school.

Proud Daughter

My father, Bernard “Bernie” MacDonald Holmes, was born in 1924 in Benito, Manitoba. He and his 10 siblings were raised by their parents, Dan and Vera, on a farm in the Thunderhill district. Bernie joined the army at 19 and went overseas in 1943, becoming a member of the 1st Canadian Armoured Carrier Regiment, also known as the Canadian Kangaroos.

Bernie was a tank driver. The tanks he and his mates operated had their internal guns removed in order to carry more men—approximately 11 soldiers could be transported safely without those guns. He was stationed in France and then Holland, where he experienced the celebrations on May 5, 1945—Liberation Day for the grateful people of the Netherlands—and on May 8, VE-Day, which marked the end of the war in Europe. As there were many thousands of men and women serving overseas, Bernie had to wait his turn to come home. It took nine months before he was shipped back to Canada, during which time he took a job in a library in London.

He and my mother, Madeline Puffer, were married in May 1947, and they, along with my three siblings and me, lived on a small farm in Manitoba for many years. The family moved to central Alberta in 1970, where I still reside, as does my brother, Keven.

Sadly, Dad passed away on February 12, 2004. —Daylene Shaw, Rocky Mountain House, Alberta

Proud Son

My father, David Sinclair Wilkinson, was born in Montreal on June 27, 1916, and was a member of the 17th Duke of York Royal Canadian Hussars Army Reserves. He enlisted in the Royal Canadian Airforce (RCAF) on June 6, 1942, and was posted to the auxiliary training facility at No. 5 Manning Depot, where he followed the required military training for newly enlisted members.

After completing the air force training requirements of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), including Initial Training School (ITS) and Service Flying Training (SFTS), he was promoted to Leading Aircraftsman (LAC). This was followed by Bombing and Gunnery Training (BGS), from which he graduated as Air Bomber, and Air Observer Training (AOS), from which he graduated and was commissioned as Pilot Officer on June 11, 1943.

Later that month, Dad was sent overseas to team up with Britian’s Royal Air Force (RAF). He was promoted to Flight Lieutenant on November 1, 1943, and to Flying Officer on December 11, 1943. Be- tween October 27, 1943, and October 25, 1944, he completed 30 sorties as an air bomber, which included attacks on many tactical targets in the occupied countries of France and Holland, and others on strongly defended German targets, such as Leipzig, Stuttgart, Frankfurt, Essen and Berlin.

In the words of his superior, “His work as Air Bomber in Squadron 460 was of the highest order and his consistent skill and aptitude for his job were in no small part instrumental in his crew’s fine record of precision bombing. His determination to press home all attacks despite any opposition encountered has been outstanding. On long trips over enemy territory his calmness and courage gained the admiration and the confidence of all the crew. In reward for his outstanding gallantry and most praiseworthy services, I recommend the award of the Distinguished Flying Cross.“

Awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) on February 5, 1945, he was invested with the award by King George VI on June 27, 1945. He married the love of his life, Ruby, a member of the RAF’s Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), on June 9, 1945, in London, England. He retired from the RCAF on July 30, 1946, upon his return to Canada, and Ruby arrived here a month later. Dad passed away on August 22, 1981. —David Wilkinson, Ottawa

Here’s how the Highway of Heroes Tree Campaign is transforming our continent’s busiest highway into a living tribute.

Always Ready

Lee-Anne Quinn has the distinction of being the Honorary Lieutenant Colonel of the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment, one of Canada’s most prestigious infantry regiments that forms part of 33 Canadian Brigade Group within Land Force Central Area / Joint Task Force Central.

She is the first female chosen, in the regiment’s 150-year-old existence, and I asked her to tell me about her life in service.

“There is no greater honour than to care for an injured soldier,” Lee-Anne says. “It is a humbling experience as a nurse practitioner as you become their mother, padre, mental-health support and confidante.”

Lee-Anne has been asked by many people why she decided not to go to med school instead, and her response is always the same.

“If I became a physician, then I could never aspire to be Florence Nightingale! My ultimate hero. As nurses in the field, we are the first up and the last to go to bed,” says Quinn. “I have 22 years in the Canadian Forces. Absolutely loved my career and all of the experiences it offered and would not change a thing. I did missions in Somalia, Rwanda, former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan and several postings to First Nations and Inuit communities.”

For her work in isolated First Nations and Inuit communities in Northern Ontario, Quinn did in fact win the prestigious Nightingale Award in 2003.

She received the Governor General’s Award (Medal of Military Merit) in 2007 and the Queen’s Jubilee Medal in 2012.

“No one ever told me it was going to be easy,” said Lee-Anne. “I was a broken soldier at the end of my career but the Canadian Forces looked after me well and I am here to talk about my experiences today. I believe every human deserves to be treated humanely and we as humans need to do a better job at maintaining world peace.”

My brief encounter with Lee-Anne left an inspirational impact. The combination of caring, kindness, dedication and duty de- fined the humble woman I met.

May Canadians take comfort in the fact there have always been, and always will be, dedicated souls who choose careers as military nurses in the Canadian Forces. Lee-Anne’s allegiance and “always ready” attitude are to be honoured and remembered. —Lynn C. Bilton, Cobourg, Ontario

Long-Awaited Return

My father, Private Felix M. Perry, was born in St. Louis, P.E.I., on August 18, 1909, to French Canadian (Acadian) parents. His father later moved the family to a farm in Hunter River, P.E.I. In June of 1940, Felix heeded the call and volunteered to join the Canadian army to aid the Allied nations against German and Italian forces. He enlisted with The Prince Edward Island Highlanders and was shortly after relocated to Nova Scotia. While in Europe, however, he was transferred to The West Nova Scotia Regiment, more commonly known as the West Novies.

After basic training in Halifax, his unit was sent to Newfoundland and spent over two years (August 1941 to April 1943) in training before overseas deployment. While in Newfoundland, he met a young,

18-year-old girl, named Edna Dobbin, who was the sister of a pen pal he’d been corresponding with. Private Perry and Edna got married in July of 1942 and just prior to being shipped away, their daughter Mabel was born. On November 25, 1943, his battalion embarked for England and would eventually arrive in Italy in March 1944. He trained in infantry and served as a machine gunner in a support battery. He was also qualified as a courier driver for short periods and saw combat in Italy and France. In fact, Veteran’s Affairs Canada has him listed serving 21 months in Italy and North West Europe. It would be two long years before he would see his beloved wife Edna and young daughter again.

Private Felix Perry survived the war, seeing service in Italy, France, Belgium and Holland before disembarking from France in March of 1945 to return home where he was honourably discharged on September 26, 1945. Felix and Edna were once again reunited and lived in several locations across Canada before finally settling down in Dartmouth, N.S., to raise a family of nine children. He died in 1981 at the age of 71.

My book Red Soil, tells Private Perry’s story from his last day on the farm to the bloody battlefields of Europe, to his eventual return home and reunion with his family. —Felix L. Perry, Halifax

Answering the Call

The year was 1943 and the Beddington family of Coleman, Alta., was gathered together prior to the young men going overseas. Pictured (from left) is my uncle Fred Jr. (20), my grandfather Fred Sr, (49), my uncle William (18) and my dad Roy (23). Seated is my grandmother, Emily (44). Fred Sr. was in the RCAF at No. 8 Bombing and Gunnery School in Lethbridge, Alta., where Emily also worked in the Officers Mess as a steward. In 1945, Roy and Fred Jr. ended up in the same platoon in the Regina Rifle Regiment, fighting in Germany, where Roy was wounded in the Battle of the Hochwald Gap.

After convalescing in Belgium, Roy was back in action, although re-badged as a member of the Calgary Highlanders. Fred Jr. soldiered on till war’s end in the Regina’s. William served in the RCN in a corvette during the Battle of the Atlantic, and also participated in the D-Day landings as a crew member on an LCI (Landing Craft Infantry). All returned home safely in 1946, but are now all deceased. William in 1951, Roy in 1971, Fred Sr. in 1980, Emily in 1997 and Fred Jr. in 2007. We shall always remember them. —Roy Beddington, Bath, Ontario

Check out these true stories of Canadians who helped make D-Day a success.

Canada’s ‘Youngest Soldier’

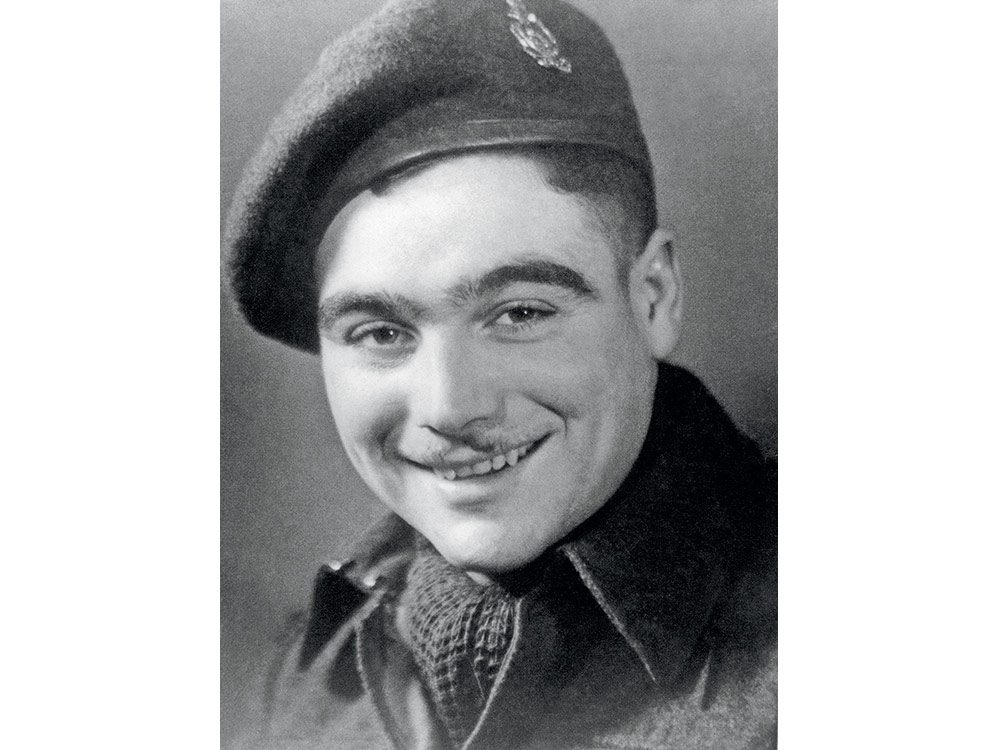

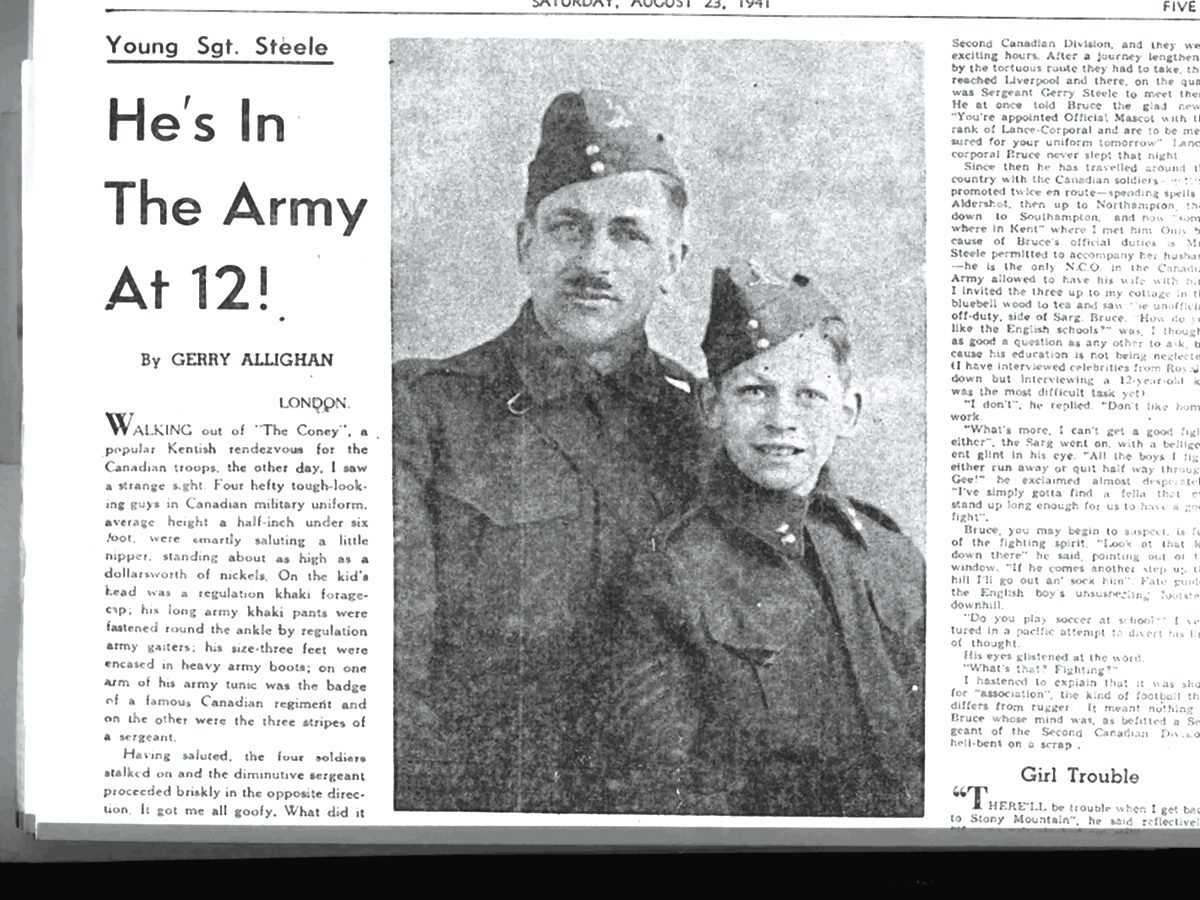

On September 7, 1939, just three days before Canada declared war on Germany, my paternal grandfather enlisted in the Canadian Army. Three months later, he told my grandmother that he was being shipped to England. She was heartbroken, so heartbroken that she raised enough money to take her and my dad by train to Halifax and then by ship, the Duchess of Bedford, to England. She arrived in Liverpool in March 1940 with just $68 tucked in her brassiere.

Shortly after arriving, my dad, Bruce Steel, became the official mascot of the Canadian Overseas Army and Canada’s “youngest soldier” at nine years of age. He was given the rank of Lance Corporal and for the next four years, he paraded and trained with the First Division across all of En- gland, marching proudly at the front of his regiment and on several occasions was reviewed by royalty. Upon his re-turn to Canada in 1944, Dad completed high school, joined the Canadian Armed Forces in 1949 (where he spent the next 24 years until his retirement in 1974), married my mom in 1952 and had four daughters.

He and my mom presently reside in Brentwood Bay on Vancouver Island. —Debra Patterson, Stony Plain, Alberta

Read the incredible true story of Canada’s WWII sniper squad.

Leading the Way

My uncle, Errol Stewart “Bubby” Gray of Amherst, N.S., served with the North Nova Scotia Highlanders, 1st Battalion, RCIC as a Captain during the Second World War. The regiment stormed the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, June 6, 1944, and fought their way inland through fierce resistance. Up to this point, the unit had proceeded with great dash and vigor. The advance guard had cleared out a large number of enemy pockets, without suffering any casualties, and were further inland than any other troops at this time. Bubby had displayed unusual swiftness and initiative while commanding the vanguard, advancing as far as Authie on June 7, 1944. He exhibited great personal courage on a number of occasions by moving forward on foot, while under fire, in order to maintain progress.

When being fired upon in Les Buissons, he pressed on by leading his men through open field and successfully destroying an enemy 88-mm gun and rocket projector in the process. His efforts in directing and leading his supporting infantry were again successful in capturing another 88-mm gun in Buron. On July 8, 1944, Operation Charnwood was launched and The North Nova Scotia Highlanders planned to attack the vicinity of Authie, two kms west of Caen, however German shelling caused heavy casualties among the Canadian troops. Authie was eventually conquered in the afternoon, however it came at a cost as seven Sherman tanks were destroyed, and 160 Canadian and British lives were lost, including that of Major Gray, who was killed in action that day. He was 24 years old. The outstanding courage, aggressiveness and devotion to duty displayed by Errol Stewart “Bubby” Gray, throughout the advance, was a large factor in pressing forward against enemy ranks and because of his many acts of her- oism, gallantry and distinguished conduct in the field, Bubby was awarded the Military Cross and promoted to Major after his death. He is buried in the Beny-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery, in France.

He was survived by his parents, John James and Anna Gertrude Gray and three brothers, John, Edward and Jim.

“At the going down of the sun, and in the morning, we will remember them.”

I wish to thank my uncle, Air Commodore Robert John (Spotty) Gray—Bubby’s oldest brother—for providing some information for this piece. —William Gray, Halifax

Quiet Dignity

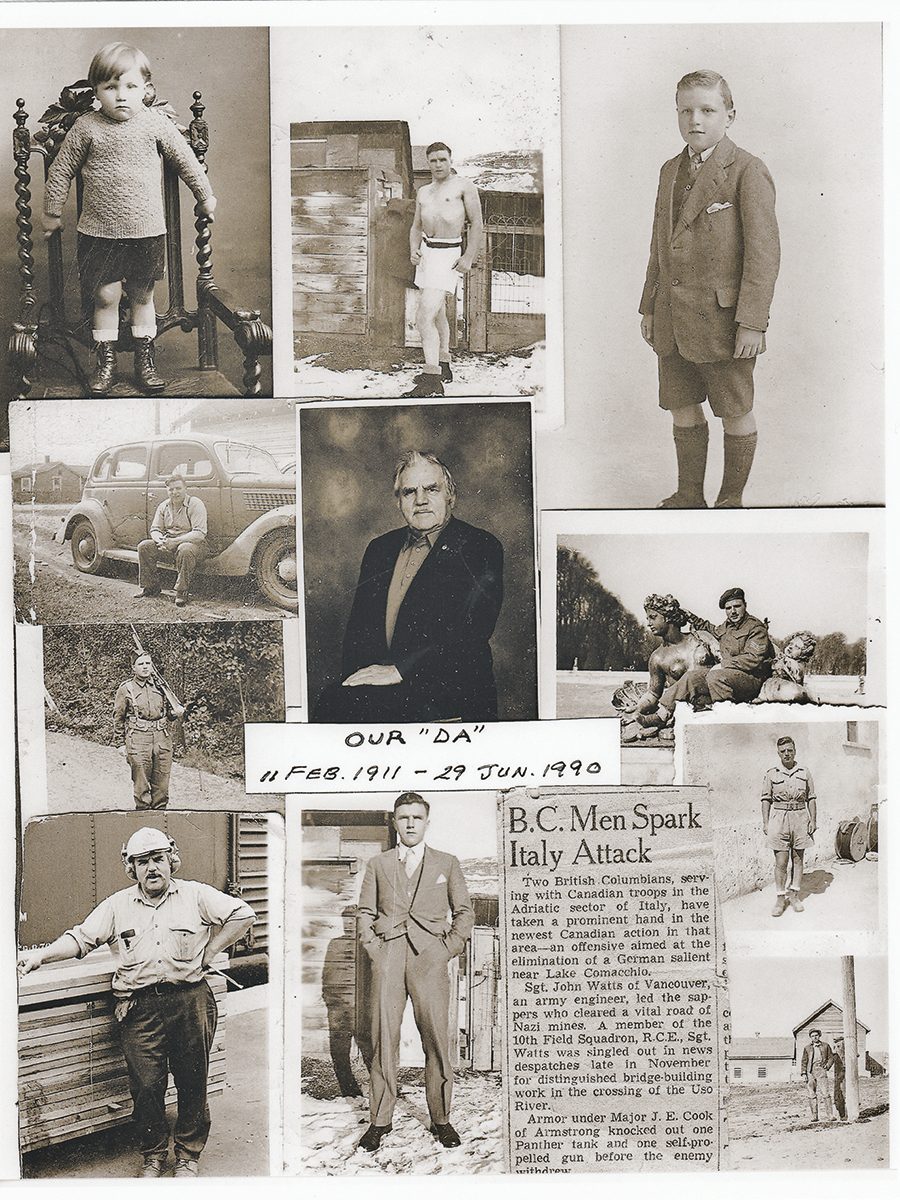

My father, John Watts, was born on February 11, 1911 in London, England and came to Canada with his mother, Florence Ethel, when he was 14 years old. John’s father, Percy, died when John was three. Percy was with the British Army in India and died of complications arising from his service in that country. When John was 16, he ventured out on his own, working at anything and everything he could in order to supplement the family’s earnings. He was a grocery delivery boy, whistle punk in a logging camp in Sooke, B.C., and a farmhand before riding the rails to Alberta to work on threshing gangs on farms and ranches. In 1933, he met Dora Coombe (my mother) in Rockyford, Alta., and they were married in 1936.

In 1937, John and Dora moved into their own homestead in Crammond, just north of Olds, Alta., and lived there until John joined the Royal Canadian Engineers, 5th Division, 10th Field Squadron of the Canadian Army in October 1940. He left for England one year later. John was involved in the Italian Campaign and was stationed in France, Holland, Belgium and Germany. He was mentioned specifically for brave actions by himself and his squad in the Vancouver newspapers on a number of occasions during the war.

He was the recipient of the Italy Star, France and Germany Star, the 1939-1945 Star, the Defence Medal, the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal and clasp, and the War Medal, 1939-1945. He left the army as a sergeant in 1946. My mother, along with my brother Ken and I, left Alberta in December 1940, and moved first to Pitt Meadows and later Hammond, B.C.

Upon John’s arrival in Hammond, he soon found employment with the Hammond Cedar Company, and later British Columbia Forest Products (BCFP), where he remained until his retirement in March 1976. Our family grew to include another daughter, Wendy, and two more sons, Raymond and Barry.

John was a quiet man. He was modest to a fault. He never demanded respect but earned it easily. He was also not a religious man but lived by the Commandments with ease. He was very compassionate and empathetic, and always had time to listen and lend a helping hand. John’s passing was a great loss to us, and the world is a poorer place for his absence—that is the finest legacy that any man can leave. —Joan Steadman, Chilliwack, British Columbia

Here’s how one Alberta family made it their mission to return a lost WWI campaign medal.

A Lifetime of Service

My father, Arthur Fredrick Haley, is a 105-year-old Veteran of World War II living in Wiarton, Ont. Art joined up in 1943 despite having a wife and a young family of three. After preliminary training at Camp Borden in Ontario and CFS Debert in Nova Scotia, he shipped out on the SS Île de France, reaching Grenoch, Scotland, on May 8, 1944. He received further training in England as a sniper with the Queen’s Own Rifles. On July 30, he crossed the English Channel, landing north of Caen, France.

He became a replacement member of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders as a newly minted stretcher bearer. His infantry division advanced against the Germans at Falaise in France, then advanced to Boulogne and on to Scheldt Estuary in Holland to liberate the Dutch. Art and his son, David, attended both the 50th and 60th anniversaries of the liberation of Holland. While overseas, Art wrote many moving poems (see his poem Falaise at right) and continued this hobby when he returned home in 1946.

He has published two books of poems: Haley’s Comments and The Return of Haley’s Comments, as well as his autobiography, No Regrets. Art wrote more than 300 letters home to his beloved wife, Alberta, which she kept. Art has volunteered most of his adult life and has been presented with many certificates of appreciation, including the Caring Canadian Award in 2001, presented by Adrian Clarkson; the Veterans Affairs Commendation Award in 2007 and the Bruce Peninsula Volunteer Award.

He spent 20 years volunteering at the local school as a tutor and in the library. Art is also an 80-year member of the Masonic Lodge. He was inducted into the Billy Bishop Hall of Fame in 2001. Art’s latest awards include the Diamond Jubilee Medal in 2012 and the Legion of Honour from France in 2014. In November 2018, his granddaughter presented him with a Quilt of Valour. Art and his wife, Alberta, who died in 1994, were married for 56 years and had six children, 15 grandchildren, 16 great-grandchildren and three great-great grandchildren.

Art now resides in a long-term care home but is very alert and is enjoying being looked after. His life’s philosophy is “Think positive, have a sense of humour and stay healthy.” —Jeanette Jackson, Wiarton, Ontario

Read the incredible story of how a metal shaving kit saved this Canadian soldier’s life in WWII.

Rest in Peace

My brother, Wallace, was born on July 14, 1923 to David M. Ross and Kate L. Ross of Dirleton, Alta. He enlisted in the RAF in 1942 and, after training as a tail gunner, was sent overseas and based at Skellingthorpe, England with RAF 50 Squadron. On a scheduled bombing run to Lille, France, their Lancaster LM 429 was shot down and crashed on the night of May 11, 1944 near Oostleteren, Belgium, resulting in the loss of all crew members including Don Ball, air gunner age 22; Frank McFarlan, PO, age 20; James Elliott, navigator F/Sgt, age 20; Leonard Craven, air gunner, age 22; Doug Ingram, flight engineer, age unknown; Robert Cunningham, gunner, age 22; Wallace Ross, PO air gunner, age 21. They rest in Collective Grave 11 in Oostvleteren Churchyard in Belgium. The headstone reads, “Safe in the Arms of Jesus in Loving Memory of Wally from us all at home—Mom.” —Harvey Ross, Calgary

Find out how Cree code talkers from Alberta helped win WWII.

Proud Daughters

Our father, George Alfred Masters, was born in Kent, England, and came to Canada as a young man. During World War I, he signed up with the 204th Beaver Battalion, was transferred to the 3rd Battalion Royal Regiment and became a corporal. He participated with the Canadian Army at Vimy Ridge, Hill 70, Passchendaele, Amiens, Arras and on the vaunted Hindenburg line, which was broken by Canadians. He was wounded six weeks before the November 11 Armistice and was sent back to Reading, England.

During the Second World War, after serving 18 months, he was transferred to the Veterans Guard of Canada, where he was engaged in guarding prisoners of war in Winnipeg, as well as Espanola, Monteith, Nipigon, Windsor and Petawawa in Ontario, until the end of hostilities. He joined the Canadian Corps of Commissionaires in 1948 and, for the most part, was stationed at Sunnybrook Military Hospital in Toronto until his retirement.

He was presented with the Canadian Corps of Commissionaires Long Service Medal for his 15 years of peace-time service at the hospital. —Gladys Masters, Richmond, Ontario, and Rose Sutherland, Stayner, Ontario

Here’s the incredible story of Private David Pennington, the veteran of Veteran, Alberta.

Drafting a New Plan

Clarke Edgar Sheppard was born in Toronto on May 10, 1923. He joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in October of 1942, with hopes of becoming a fighter pilot. Unfortunately, poor vision in one eye (due to looking directly at a solar eclipse as a boy) meant he was not eligible for any flight crew positions. He even memorized several eye charts in an effort to fool the doctors, but was caught out every time. Once the air force determined that he was a qualified draftsman, he was stationed at #4 Maintenance Unit at Scoudouc, N.B., designing airframe modifications for Canadian aircraft. He served until his discharge in June 1945. He married Ailene May Jackson in December of 1944 and, in 1978, they retired to Sackville, N.B. Clarke passed away in June of 2011. Ailene passed away in July of 2014. —Norm Sheppard, Sackville, New Brunswick

Don’t miss these powerful poppy pictures for Remembrance Day.

All in the Family

My grandfather, John (Jack) Davey, was born in 1888 in Somerset, England, and immigrated to Victoria in 1912. With the outbreak of World War I, he enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Forces on September 23, 1914, the day after his 26th birthday. As a corporal in the 7th Battalion, he fought in the second battle of Ypres and was wounded on April 23, 1915. Two days later, he was found by enemy soldiers and taken prisoner; his wounded leg was partially amputated in the POW camp. Five months later, he was repatriated to England where a further amputation of his leg was performed. He returned to Canada in February 1916 and was given a medical discharge on April 23, 1917. Ten days later he married his sweetheart, whom he had faithfully written to during his time overseas. He became a lifelong member of the War Amps Society of Canada, serving as the president of the Victoria Branch for many years. He worked for the B.C. Civil Service for over 27 years and passed away October 13, 1962.

His eldest son, my uncle, Flight Sergeant John Vernon Davey, enlisted in the RCAF in June 1940 and flew Kittyhawks over the North African desert in support of the 8th Army Desert Rats. On May 17, 1942, at age 24, he was killed when his plane was shot down; his plane and body were never found. His name is inscribed on the Alamein War Memorial in Egypt. —Corinne Davey, Calgary

Next, check out these powerful Remembrance Day quotes to share on November 11.