Thoughts of the First World War bring to mind images of mud, shell holes and the horror that resulted in the loss of at least 60,000 Canadian soldiers’ lives, most of them very young. Fortunately, amid the gloom of the trenches, where every third man was wounded and every tenth killed, a rare glimpse of beauty was available. Delicate, embroidered silk postcards from France and Belgium were purchased by many Canadian soldiers overseas. It’s estimated that millions of cards were purchased and hurried words scribbled and sent to anxious relatives back home.

My interest in these skillfully handcrafted postcards came about by sheer accident. My father, Charles Hawkins, served overseas with the Winnipeg Grenadiers as a private from 1914 to 1918 and mailed the cards back home to his former landlady and her daughter in Winnipeg. He eventually married the daughter and years later the cards were handed down to me. By way of inheritance, I became a deltiologist (postcard collector) and have 32 of these handcrafted postcards in my safekeeping.

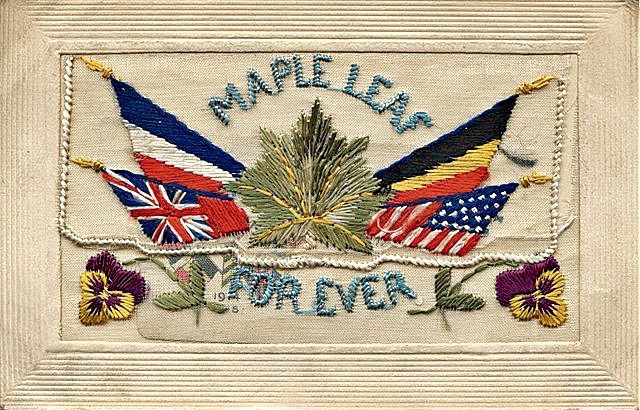

It appears no two cards were alike. The meticulous hand-stitched designs featured flags, butterflies, bouquets or peacocks. Variety of colour appeared to be the main theme, as opposed to accuracy in colour scheme. Butterflies often had the Union Jack emblazoned on their wings and poppies featured the flags of many countries in their petals.

Most of the cards included embroidered messages, some patriotic such as “Maple Leaf Forever” or “United for Liberty.” Others tended to be more sentimental, perhaps expressing thoughts the young soldier was too shy to express. Phrases like “A Kiss from France” or “For You Darling” were quite common.

Dainty pockets in some cards contained further sentiments from no man’s land to loved ones left behind. In some cases, mastery of the English language was somewhat lacking on the cards. Two of my favourites in this regard proclaim “I Don’t Forget You” and “For Your Alone.” Despite the grammar or lack thereof, I have no doubt the messages got across.

One of the few advantages afforded the troops during the Great War was free postal service. This likely contributed to the popularity of the cards. The examples I have include messages on the back, usually written in pencil, sometimes only expressing the hope that the card was not a duplicate of one already sent.

The only indication as to exactly where the cards came from was embroidered on the front. “Somewhere in France” was about as explicit as the soldiers could be. Any further indication of location would likely be deleted by the censors.

As the war drew to a close, so did the silk postcard business. It seems this industry, among others, started and ended with the war.

The final card in my collection is dated November 14, 1918. In restrained words, it reflects my father’s feeling of relief: “Just a few hurried lines to let you know I am well and it’s over at last, guess you are having some pretty exciting times in the ‘Peg these days.”