The Canal That Makes a Capital

Ottawa's Rideau Canal was never used in war, but that doesn't mean it hasn't served a purpose.

In the summer of 1976, my parents and I moved back to Canada after spending four years in Belgium. My father was an officer with the Canadian Armed Forces, and, when a military van drove us from the Ottawa International Airport to our accommodations, we took the circuitous and charming route along the Queen Elizabeth Driveway that hugged the Rideau Canal.

As the van passed bridges and landmarks, I noticed how their reflections rippled across the water. It reminded me of Bruges and its picturesque canals. There was a feeling of tranquility that few cities offer.

I strongly believe that without the Rideau Canal’s imposing beauty, Ottawa would lose so much of its natural appeal and presence as Canada’s capital. The more I’ve come to know the astonishing history and backbreaking work that went into the development of the canal, the more I’m proud that it is a part of my life.

The Rideau Canal’s History

People have often wondered why Queen Victoria, who never stepped foot on Canadian soil, chose Ottawa as the capital. The city was still an industrial eyesore with a notorious and boisterous reputation. Ezra Butler Eddy’s belching pulp-and-paper complex lined the Chaudière Falls, and Thomas MacKay’s mills crowded the Rideau River. Water was still drawn in barrels to Lowertown and Uppertown residences and businesses. The stench from the drains was putrid. Ottawa, it was noted, did not reflect a fitting symbol for the capital of a young country.

It was not the result, as myth would have it, of the Queen closing her eyes and sticking a pin on a map. The decision was due to the memory of war.

During the War of 1812, the United States launched a series of raids on Upper Canada. President Thomas Jefferson claimed victory would be “a matter of marching,” but it was not to be.

At the beginning of the war, both sides experienced financial and logistical problems. Britain concentrated its wealth on the war effort against France. The Americans faced difficulties recruiting soldiers and poor financial support from national and private banks. Nevertheless, both sides improved their military efficiencies.

The British and Canadian militia repelled the Americans and advanced to Detroit, Maryland, New York and Washington, D.C., where they burned the White House and the Capitol.

The Americans were successful in attacking shipping lanes along narrow sections of the St. Lawrence River and also penetrated the capital at that time—York, present-day Toronto. What was even more pressing was the security of Kingston further east. Kingston was strategically valuable to British supply and communications along the St. Lawrence. For the Americans, dominating Kingston would mean severing the British supply line from Lower Canada.

This reality forced the British to seek an alternative waterway as a vital safe haven for transporting supplies from Montreal to Kingston and as a means of staving off defeat.

Before action was taken to construct a new route, the war ended in a stalemate with the Treaty of Ghent. The conflict united Canadians as victors and for the Americans as an unconquered nation against Britain. Regardless, authorities in Canada realized how vulnerable their sovereignty was, and by 1816, Lieutenant Joshua Jebb of the Royal Engineers was given the duty of surveying a route for a navigable waterway critical to the nation’s defense.

Work on the Canal Begins

Colonel By laid out two settlements called Uppertown and Lowertown, separated by part of the government lands called Barrack Hill. The bush and swamps along the initial part of the route proved so impenetrable that the construction had to be done in winter, when the frozen river was more accessible.

Work on the canal began in 1826 with the implementation of several dams. To permit navigation, two dams turned Dow’s Great Swamp was into Dow’s Lake.

The initial budget underestimated the extent of supplies, manpower and time required. Numerous contractors couldn’t live up to the terms of their contracts and had to be dismissed. The unskilled labour was considered unreliable, and workers were closely monitored by the Royal Sappers and Miners. Conditions were hazardous, and the swamps were infested with malaria-carrying mosquitoes. All the excavations, forest-clearing and stonemasonry was done by hand with the aid of a few draft animals. Rock was drilled and blasted with an unstable mix of nitre, sulphur and charcoal. The large stones that make up the locks were set in place using simple hand cranes.

Much of the skilled rock work was completed by British stonemasons and French-Canadians who had experience on other lock projects.

Unskilled labour was done by Irish immigrants and French-Canadians. Thousands of men per year worked on the canal. By the time of its completion in 1832, a thousand workers had died by yellow fever, malaria and on-site accidents.

An Engineering Triumph

Colonel By didn’t agree with the original concept of locks being 100 feet long by 22 feet wide. He felt the locks would be more accommodating if they were 50 feet wide to handle the new naval steamships. A compromise of 134 feet long by 33 feet wide was finally reached.

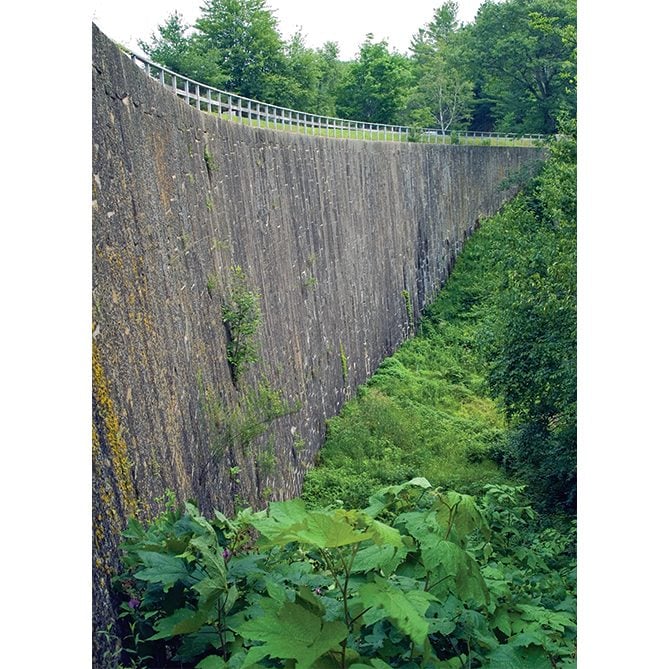

He also decided to turn the Rideau into a slackwater system, which meant flooding the regions between one lock and the next to navigable depths, necessitating the construction of water control dams. The dams were an engineering triumph in the 19th century. A testament to the difficulty, Hog’s Back Dam collapsed twice before it could be completed.

Based on records from RideauInfo.com, Colonel By divided the Rideau into 23 work sections, and contractors were meant to complete the work required for each section within a two-year period. By 1831, construction had essentially been completed, with 47 masonry locks and 52 dams covering over 200 kilometres of length. The Rideau Canal was acclaimed as one of the most significant engineering feats in history and remains in perfect working order today. It is reported by The Friends of the Rideau that the average lock lift uses 1.3 million litres of water.

Though it was a major engineering accomplishment, Colonel By was chastised by the British government for cost overruns of 60 per cent. The final cost was £822,000, equivalent to about $150 million today, according to the Historical Society of Ottawa. This price still did not include a further 19 kilometres of required canal cuts, channel dredging, surveying and route clearing, according to RideauInfo.com. Though Colonel By was exonerated by a parliamentary inquiry, he never received formal commendation in recognition of his achievement and he spent the remaining years of his life attempting to clear his name.

The Rideau Canal was never used as a military supply route.

How Ottawa Became Canada’s Capital

Queen Victoria was asked in 1857 to make the controversial decision as to the new capital. Her surprising choice of Ottawa lay right on the border between Upper and Lower Canada, by now the united Province of Canada, and had a unique blend of English and French. It was more easily protected from the Americans than any site along the St. Lawrence River. Finally, it had transportation access to Montreal and Kingston via the Rideau Canal. The following year, the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, laid the cornerstone of the Parliament Building on Barrack Hill, henceforth Parliament Hill.

In 1926, the Rideau Canal was designated a National Historic Site, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the start of this momentous project. By the 1950s, the Rideau had turned into the waterway as it can be seen today. Cottages dot the serene route while larger cruisers carry tourists the extended journey down to Kingston and on to Lake Ontario. From the Ottawa River, the canal rises more than 80 metres to the Rideau Lakes, then descends 50 metres to Kingston. There, you can continue east to the Atlantic Ocean, west to Lake Ontario and the Great Lakes, or south to the New York State Canal and the Erie Canal. The waterway was the primary reason towns such as Manotick, Merrickville (known as “the jewel of the Rideau”), Smith Falls, Perth, Westport and Kingston flourished as new communities for the waterway’s military and labour force and, later, as thriving commercial centres.

In 2000, the Rideau Canal was given the distinction of becoming a Canadian Heritage River in recognition of its outstanding engineering history and recreational value. Seven years later, the canal was inscribed as a World Heritage Site. (Here’s every UNESCO World Heritage site in Canada.)

A study showed that the canal contributes over $24 million to the GDP and sustains hundreds of jobs. Every year, 90,000 boats pass through its locks, and the annual budget for its operation and maintenance is millions of dollars.

The Rideau Canal opened up the region and created the city of Ottawa. Regardless of the cost, the Rideau Canal is a living part of Canada’s heritage, something to remember as the nation commemorates the waterway’s 190th anniversary this year.

Next, check out 10 Canadian castles worth exploring.