This Was the Deadliest Forest Fire in Canadian History

The Great Matheson Fire of 1916 killed 223 and ushered in Ontario’s first forest firefighting measures.

July 29, 1916 began as a hot, dry, hazy day in the northern Ontario town of Matheson. Despite the smoke in the air, residents went about their usual Saturday morning chores—the smell of burning wasn’t unusual in the tiny settler village, built along the new Temiskaming railway line. Encouraged by the government to set up homesteads, European immigrants cleared the land by burning the dense brush. With no rain for weeks, several small fires on the outskirts were already beginning to grow, but the townspeople had no reason to believe anything was out of hand.

Around midday, William Dowson noticed something in the sky as he took his lunch break from a job mixing concrete. “One of the workmen called our attention to a black cloud over the treetops,” wrote the 21-year-old bricklayer in his diary. “We all decided it was a thunder cloud and paid no attention, until a wave of heat and a thick pall of smoke struck our shed with such force that it almost collapsed.”

The exact origins of the fire are still a mystery—most say high winds whipped a number of smaller fires into one huge firestorm. Others blamed the railway companies, which often used dynamite to blast through rock. Whatever the case, a gigantic inferno with a front over 60 kilometres long raced eastward at 40 to 60 kilometres per hour, totally unstoppable.

Dowson saw panicked townspeople filling buckets and basins with water from the Black River in a futile effort to douse the oncoming flames. As the fire rolled over one town after the next, some managed to survive by wading chest deep into the river, breathing through wet clothing to filter the searing hot smoke. Some climbed on board a boxcar train that punched straight through the wall of fire, while people stuffed wet cloths between the slats. Dowson took cover huddling under a makeshift shelter made from boxes and a wet tarpaulin.

By the time the blaze died down several days later, it had incinerated more than 500,000 acres (an area the size of Toronto, Montreal and Calgary combined). Entire communities were razed: Matheson, Iroquois Falls, Nushka, Porquis Junction, Kelso, and Ramore, with extensive damage to Homer, Monteith and Cochrane. Officials accounted for 223 dead, but with many bodies burned beyond recognition, it’s thought the toll may have been closer to 500—prospectors, trappers and drifters often passed through frontier towns in search of their next adventure.

Dowson walked back into Matheson to find a scorched hellscape where the town once stood, corpses littering the ground. “Swept away,” he wrote. “All of it.” The neighbouring town of Nushka was also wiped off the map, with only eight survivors. It was later rebuilt as Val Gagné, after Catholic priest Wilfrid Gagné. He was credited with trying to save 63 parishioners by leading them to a narrow trench by the railway tracks. Tragically, as the fire roared over the town, they all suffocated from the smoke and carbon monoxide.

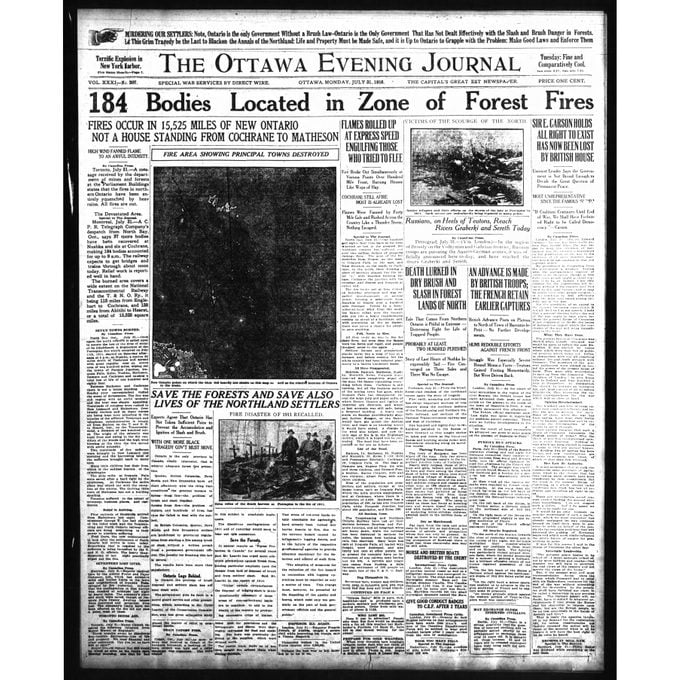

The Matheson fire shared front-page news with World War I for days, and outrage spread over the lack of fire protection. At the time, Ontario was the only province lacking any regulation of the practice of burning brush to clear land. What’s more, it wasn’t the first devastating forest fire in the region—five years earlier, the Great Porcupine Fire of 1911 swept through 200,000 acres and killed 70.

All of that changed a year later with the introduction of the Forest Fires Prevention Act of 1917, a landmark piece of legislation that created Ontario’s modern fire control system. Along with requiring permits for all land-clearing fires, the government began investing in the prevention, detection and suppression of forest fires, creating a provincial firefighting corps and hiring 1,000 rangers to patrol the lands. A network of hundreds of fire lookout towers were built across the province, where watchmen surveyed the horizons until the 1960s, when aerial fire detection planes took over.

Today, all that remains of the 1916 tragedy are the artifacts housed in the Thelma Miles Historical Museum in Matheson, and a memorial plaque in the town centre. While the devastation caused by the fires in Matheson and other Northern Ontario communities brought many improvements to the way we understand and respond to forest fires, the horror of that July day remains seared on our collective conscience.

Next, find out why 1816 is known as the year Canada didn’t have a summer.