Tseax Cone Eruption, British Columbia

Late 1600s or early 1700s

More than 300 years ago, Canada’s deadliest volcanic eruption killed 2,000 Indigenous people in what is now northwestern B.C. The worst known geophysical disaster in our country’s history, the eruption produced a plume of toxic smoke and a river of lava that destroyed two villages and suffocated thousands of people, according to Nisga’a oral history. Legend tells of a great trembling and a rush of fire and smoke, sent down the mountain by an angry Creator to punish a group of children for harming salmon.

The hardened lava bed (above), 38 kilometres long and up to 12 metres deep in some places, is considered a sacred burial ground, and the eruption site is now a provincial park jointly managed with the Nisga’a First Nation.

Cascadia Earthquake, British Columbia

January 26, 1700

The Tseax eruption might actually have been triggered by the biggest known earthquake in Canadian history, with a magnitude estimated at 8.7 to 9.2 on the Richter scale—about the same intensity as the quake that caused the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. The cataclysmic shock struck at night, according to Indigenous oral history, rupturing a 1,000 kilometre-long fault line from Vancouver Island to northern California, plunging coastal forests into the sea, and killing between 2,000 and 3,000 people. Resulting tsunamis struck both the west coast of North America and Japan, where written records date the event to January 26, 1700. Indigenous art and mythology from Vancouver Island tell stories of a great battle between a thunderbird and a whale, an allegory for the quake.

Seismologists warn the Cascadia fault line is due for a big one soon—megathrust earthquakes have happened there every few hundred years.

Don’t miss these natural disaster survival tips from a Canadian Red Cross volunteer.

Great Newfoundland Hurricane, Newfoundland and Labrador

September 9, 1775

Canada’s deadliest hurricane on record claimed 4,000 lives, most of them sailors from England and Ireland who drowned off the southern and eastern coast of Newfoundland. Then a British colony, Newfoundland’s Grand Banks were some of the richest fishing grounds in the world. In late August, a violent storm had pummeled the eastern seaboard just as the American Revolutionary War was in full swing. On September 9, a second tempest wrecked as many as 700 boats, including two Royal Navy schooners, and caused a storm surge of six to nine metres at St. John’s harbour. “The shores presented a shocking spectacle for some time after, and the fishing nets were hauled up loaded with human bodies,” wrote one observer. Most 18th-century ships were no match for the Atlantic’s most powerful storms, and an estimated three out of every five New England sailors died at sea each year.

Find out why historians call 1816 “the year Canada didn’t have a summer.”

Nova Scotia Hurricane, Nova Scotia

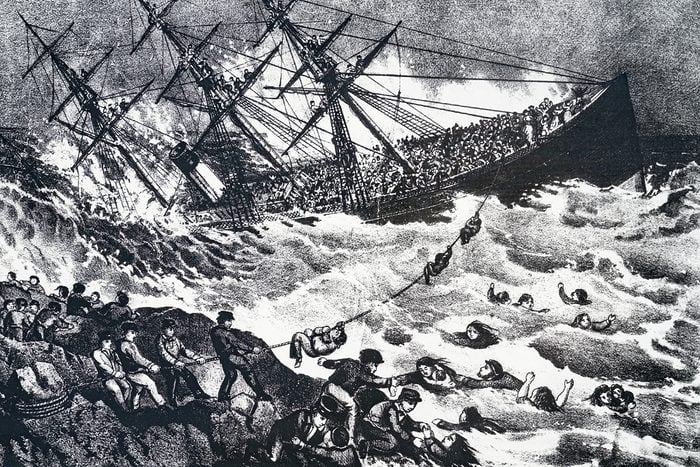

August 24, 1873

Also called the Lord’s Day Gale, this relatively weak hurricane—a Category 2 by modern estimates—was still deadly, destroying 1,200 boats and 900 buildings, causing floods and high winds, and killing an estimated 600 throughout Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. (Although the official death toll was 223, it’s thought many more sailors were lost at sea). Despite triggering the first-ever hurricane warning issued by the U.S. Weather Bureau as the storm crawled up the coast, most Maritimers were unprepared.

Earlier that same year, Nova Scotia had endured another major seafaring tragedy: the sinking of the S.S. Atlantic (above), a White Star ocean liner that crashed on the rocks around the Halifax harbour on April 1, killing 535.

Read up on the most famous shipwrecks in Canadian history.

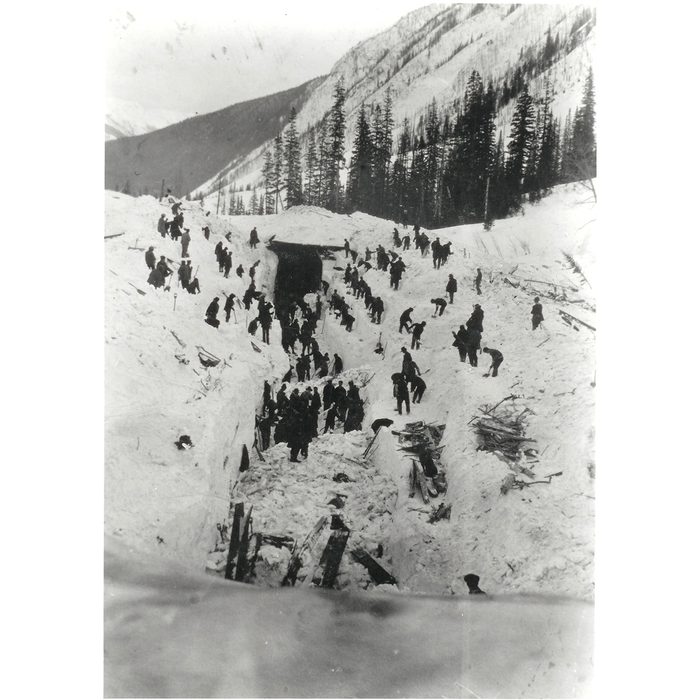

Rogers Pass Avalanche, British Columbia

March 4, 1910

The Canadian Pacific Railway’s transcontinental railroad linked Canada from coast to coast in 1885, making the company one of the most powerful in the country. There was, however, one problem: the train journey through the Rockies to Vancouver depended on one perilous passage through the Selkirk Mountains. Rogers Pass near Revelstoke was prone to heavy snow and avalanches that buried the tracks up to 12 metres deep, so crews were often called in to clear the way. Just before midnight on March 4, a huge snowslide hurled a 91-ton locomotive off the tracks and buried 62 men, half of whom were Japanese workers. Their bodies were recovered frozen upright in position, in a similar manner to the victims of Pompeii. CPR soon abandoned the pass, opting to bore a tunnel through Mount MacDonald.

Here are more fascinating Canadian Rockies facts most people don’t know.

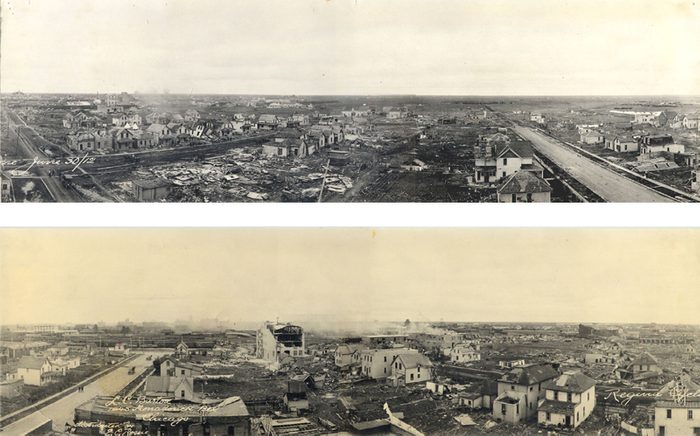

Regina Cyclone, Saskatchewan

June 30, 1912

Canada’s deadliest tornado tore through Regina one Sunday afternoon in June of 1912, beginning with strange-looking green funnel clouds just south of the city. By accounts, it levelled most of the business district within 20 minutes with winds up to 400 km/hour, flattening buildings and causing houses to explode from the pressure. Twenty-eight people were killed and 2,500 left homeless. “Automobiles had been tossed around like so many feathers, and in many cases were twisted up into ball-shaped masses,” reported one eyewitness. “In Victoria Park not a tree or shrub was left with bark on them.” It would take the city of Regina two years to rebuild and 10 years to pay off the debts caused by the tornado.

Read up on the terrifying events of July 31, 1987, when the Black Friday Tornado hit Edmonton.

Great Lakes Storm, Ontario

November 7-10, 1913

Also called the White Hurricane, the storm that battered all five Great Lakes in November of 1913 caused devastation and death on both sides of the border. An extratropical cyclone that formed when two major storm fronts converged over unusually warm lake waters, the gale overturned ships with 10-metre waves and wind gusts of 140 km/h, downed power lines, flattened forests, and dumped 50 centimetres of snow across much of southern Ontario. At its peak, the tempest raged for 16 hours straight—rare for a storm of that magnitude. With 250 dead, many of them unidentified sailors who later washed up on shore, it was the deadliest natural disaster in the Great Lakes region.

Discover what it was like on the coldest day in Canadian history.

Ice Storm, Ontario and Quebec

January 4-10, 1998

The massive ice storm that drove 600,000 Canadians out of their homes was one of the worst natural disasters in our history—not only in geographic coverage but cost, which topped $5 billion. From Kingston, Ontario to Quebec’s Eastern Townships, some areas were covered with up to 10 cm of ice pellets and freezing rain, toppling hydro lines and leaving residents without electricity or heat in the dead of winter. The federal government ordered the largest-ever peacetime deployment of troops, with 15,000 Canadian Forces personnel called in to provide shelter and medical care, clear roads and deliver supplies.

Take a look back at the worst Canadian snowstorms of all time.

Southern Alberta Floods, Alberta

June 19, 2013

The most catastrophic flooding in Alberta’s history caused as much as $6 billion in losses and property damage, displacing 110,000 people in Canada’s largest evacuation in 60 years. Abnormally heavy rainfall of over 10 cm in a day caused the Bow River, the Elbow River and the Glenmore Dam outflow to roar up to 12 times the normal rate. Officials declared a state of emergency as the flood waters gushed into downtown Calgary, filling the Saddledome up to the 10th row. Four days later, the water receded and a massive cleanup began, aided by thousands of volunteers who used social media to coordinate their efforts.

Find out why Calgary’s earned the distinction of being the “hailstorm capital of Canada.”

Fort McMurray Wildfires, Alberta

May 1-July 5, 2016

By far the costliest natural disaster in Canadian history was the wildfire that razed 590,000 hectares around Fort McMurray in the summer of 2016, incurring $9.9 billion in damages. Temperatures of 33 degrees Celsius combined with desert-dry brush created the perfect conditions for the blaze, which prompted a mandatory evacuation of 88,000 Fort Mac residents—some driving through walls of flames to get to safety. Firefighters struggled to control the inferno, which grew so large that it started producing pyrocumulus clouds and lightning. The fire eventually moved into more remote areas, but air quality and toxic ash kept many evacuees out of their homes for months. The economic and psychological impact was immense—six year later, the community is still recovering from what they call “The Beast.”

Now that you know the stories behind our country’s worst natural disasters, find out which city is officially the hottest place in Canada.