How the Yellowhead Highway Helped Unite Western Canada

The fascinating origins of the 3,500-kilometre route that now spans four provinces and dozens of beautiful parks.

This story is about weaving Western Canada together province by province. It’s about what can be accomplished when people are resourceful and passionate, have common unity and are determined to make a dream a reality. Today, as always, we know there is strength in unity. The Trans Canada Yellowhead Highway Association (TCYHA) has proven this beyond a doubt.

Origins of the Yellowhead Highway

This story reaches back to the 1800s, when a blond-haired Iroquois Métis traded and trapped for the North West Company, now known as the Hudson’s Bay Company. His name was Pierre Bostonais (a.k.a. Pierre Hatsination). He had yellow-blond hair, so the French voyageurs nicknamed him “Tête Jaune,” which means Yellow Head. He joined David Thompson and explored what was then known as the Leather Pass; he built a cache for his furs near the Grand Forks River, at what is now called Tête Jaune Cache.

In the fall of 1828, near the headwaters of the Smoky River, Pierre Bostonais and his family were killed, along with others, by the Danezaa (Beaver) tribe in retaliation for the Iroquois encroachment into Danezaa territory. In honour of Pierre’s extensive exploration efforts, the North West Company renamed the Leather Pass “Tête Jaune Pass,” or Yellowhead Pass. Today, a magnificent highway continues to honour his name.

Around the same time period that David Thompson met up with Tête Jaune to explore the Leather Pass, Thompson also discovered a pass at the headwaters of the Athabasca River. This discovery enabled traders to follow a river route up the Saskatchewan River to Fort Edmonton, overland to the Athabasca, upstream to Jasper House and across the mountains to Boat Encampment, Fort Kamloops and Fort Vermilion. This discovery let the Hudson’s Bay leather brigades travel through the Yellowhead Pass, transporting valuable furs from the District of Saskatchewan to New Caledonia.

By the 1830s, after Fort Garry was established in Winnipeg, the eastern portion of the route was being used as a transportation corridor, connecting to the Yellowhead Pass. Red River carts struggled along this treacherous land route in 1840 to Fort Edmonton. In 1856, the Cariboo Gold Rush was in the making and the miners used the Yellowhead route to connect to the routes north to Alaska. Kate Ryan was one of the first women to undertake this adventure, travelling as a cook for the North West Mounted Police (NWMP). (Unlike America, Canada’s West had law and order prior to the influx of settlers. This was due in part to the respect and friendship between the NWMP’s Major Walsh and Sitting Bull.)

Several years later, in 1862, Overlanders travelled the treacherous Yellowhead Pass to get to Kamloops and Prince George to settle into their new homes. Catherine Schubert, the only woman, arrived safely in Fort Kamloops with her husband Augustus and three children. Not only was Catherine the only woman but she also kept it a secret that she was four months pregnant when they left Fort Garry. On October 13, 1862, she gave birth to a baby girl with the aid of local Native women.

The Direct Route

The Dominion of Canada, worried about America seizing disputed territories, passed legislation for the government to deed land and lawfully populate the West. In 1873, the NWMP established an outpost in Shoal Lake, Manitoba, on the edge of what was referred to as Rupert’s Land, or No Man’s Land.

The Dominion of Canada took control of Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company and hired Sir Sandford Fleming, a Scottish civil engineer, to survey possible routes for a new railway across the Prairies and through the Canadian Rockies. It was Fleming’s recommendation to the government that the Yellowhead Pass was the easiest, safest and most direct route to the Pacific. After all, the highest point on the Yellowhead is located in Alberta at Obed Summit (1,163.9 metres, or 3,819 feet), a mere 128.4 kilometres from the gates of Jasper National Park.

As far back as 1926, efforts were made to encourage the federal government to link the highway systems in Alberta and British Columbia. Arthur Edward Cushing Read, the postmaster at the lodge in Longworth, B.C., was a fervent supporter for the completion of the B.C. section of the highway. His passion for this project got him elected as president of the newly formed Yellowhead Highway Association with Don A. McPhee as vice president and J.O. Wilson as secretary-treasurer. In addition, Louis Le Bourdais, in his role as Minister of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) for Quesnel Land as well as Mark Connolly, MLA for Fraser Lake, provided their support to this worthy cause, along with W.A.E. Wall and George Ogston.

By the Dirty Thirties, the Yellowhead Highway Association had influenced the completion of the highway to the West from McBride to Tête Jaune Cache and north along the Thompson Route to Valemount.

With the Depression, government finances became scarce, but that didn’t stop these dedicated pioneers. Yellowhead Highway Association President Arthur Read encouraged everyone to keep up their enthusiasm and reminded them that, due to military requirements, there was hope to complete the breach to join up with the Alaska Highway.

In “Remembering,” Valerie Giles, Ph.D., notes, “Officially, the proposed Yellowhead Highway was called the Northern Trans-Provincial Highway.” She also notes that in early April 1942, the Defence Department announced they were going to start road construction “with all speed.” There was little doubt that this change of heart was, in no small part, due to World War II and the concentrated efforts of the United States to construct the Alaska Highway.

Regrettably, with the death of Arthur Read in 1945, the initiative ground to a halt and the Yellowhead Highway Association ceased to exist.

The cause was once again taken up, in 1947, by the Board of Trade, with MLA John McInnis of Fort George moving things forward. The B.C. provincial government declared it didn’t have enough men or money due to the war efforts. Undaunted, mill owners in the Prince George region took stock of what equipment they had and proposed they would donate the necessary equipment for three months to keep building the road. The boards of trade from Kamloops to McBride, in British Columbia, supported the initiative and organized a caravan from Kamloops to Blue River and back to gain public support. In July, Valemount hosted a meeting to open the road from Valemount to Blue River and agreed to provide the equipment needed to get the job done. In August, the provincial government finally coughed up $20,000 to assist in making the route passable and for its maintenance.

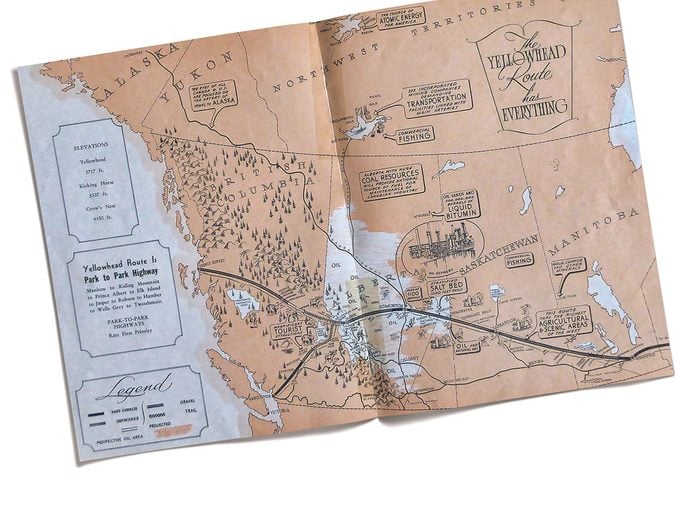

During the same period in 1947, Canada’s lack of a cross-country highway was deemed to be a national disgrace. Public opinion was now in support of action by the various governments. On July 8 and 9, 1947, the Trans Canada Highway System Association (Yellowhead Route), under the presidency of Edmonton Mayor Harry Ainlay, held a meeting in Blue River with government officials and highly respected business and professional men of the day attending. And so began the Trans Canada Yellowhead Highway Association.

A Common Goal

For more than 70 years, this nonprofit organization has represented communities along the highway from the heart of Manitoba to the shores of British Columbia and through the B.C. interior to Hope, encouraging and pushing the provincial and federal governments to obtain funding for building and maintaining Trans Canada Yellowhead Highways No. 16 and No. 5, and to encourage tourism on behalf of the dozens of communities along the corridor.

For 75 years, from The Forks in Winnipeg to the Queen Charlotte Islands and south from Valemount to Hope, more than 100 communities have worked passionately together, putting aside any local issues with one another to work towards a common goal.

Today, we can all experience the end result of these extensive efforts. Trans Canada Yellowhead Highways No. 16 and No. 5 are major transportation corridors for Canada’s goods and services, as well as a scenic and historic drive. In the April-May 2008 edition of Our Canada, I wrote an article from a tourist’s perspective about this magnificent highway, which now stretches 3,500 kilometres through the four western provinces, with direct access to five national parks, 90 provincial parks and three National Historic Sites. Through Prairie flatlands to majestic mountains, this park-to-park highway captures a huge part of Canada’s history and features some of Canada’s most breathtaking scenery. It took the courage, passion and fortitude of people like you and me to make a dream a reality.

Next, check out this photographic tour of the western provinces of Canada.