El Camino: The World’s Best Spiritual Walk

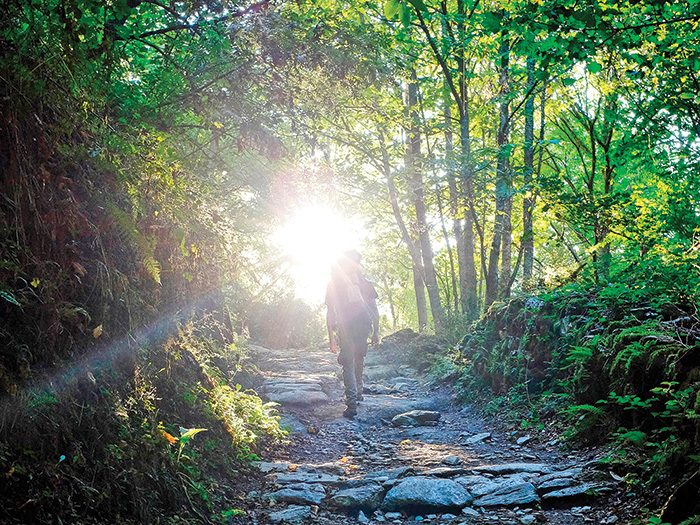

I set out on the fabled Camino de Santiago de Compostela, sorely in need of its ancient magic

I knew the weather could be bad this time of year, but I hadn’t expected snow. It came in great icy blasts that whistled in my frozen ears and obscured the forest path before me. I pushed forward, hugging my thin raincoat tighter around me. Ahead, the mountain road forked. With watering eyes, I scanned the whiteness for the one sign I knew would guide me.

Carved in a stone obelisk, a shape smaller than the palm of my hand, confidently pointed me towards safety: a small, yellow arrow.

It was my second day on the Camino de Santiago de Compostela. I was just one of the quarter million pilgrims that make their way each year on foot or bicycle to Santiago in north-west Spain. Pagan travellers may have walked the path as far back as 1000 BC; the first Christian pilgrims did so in the ninth century to pay homage to Günter James, Spain’s patron saint, who legend says is buried beneath Santiago’s cathedral. Many who walk “The Way” today make the journey for a range of non-pious motives.

I was one of them. For my entire adult life, I’d felt the need to fill every waking moment with an endless schedule of work, travel, hobbies and socializing. My racing mind never stopped, a whirlwind that gave rise to all kinds of anxieties. I needed to slow down, and I needed to be brave and do it alone.

There are several well-established routes to Santiago. I had settled on the most popular, El Camino Francés, or “French Way.” To do the entire journey means starting in Roncesvalles, southern France before arriving in Santiago nearly 800 km later, but many do only a portion. I had only eight days to complete my Camino, so I decided to start in Villafranca del Bierzo, a tiny village 200 km from Santiago.

It was a grey morning in April when the bus dropped me off on the outskirts of Villafranca. On my feet were hiking boots I had never worn, and on my back a small pack containing toiletries, socks and underwear, a sweater, a water bottle and little else. In my money belt was my prized possession: an empty pilgrim’s passport, ready to be filled with the stamps given out at stops along the way. I ducked into a bus station bar and found a very small old man quietly folding napkins.

“Excuse me,” I said in Spanish, feeling silly to be asking such a basic question. “Where is the way?”

He smiled then gently led me outside. “See that red cross across the road?” he asked. “Past that, to the left, and off you go, all the way to Santiago!”

It was drizzling as I set off, climbing a small road all but deserted of vehicles. I walked with my head up and swiveling. The land was on the cusp of spring. Rich moss and pale pink succulents blanketed the low walls that bordered the road.

The sun broke through the clouds just as the road reached a peak. Looking around, I realized I was completely alone in the landscape. I let out a long sigh as an unexpected sense of calm washed over me.

I walked until I entered the tiny stone town of Pereje. Its streets felt deserted, but I spotted a woman leaning against the grey slate wall of her tavern, so I went in and ordered a large café con leche. In coming days the thought of that sweet, milky caffeine would put a spring in my step on dull stretches of road.

As I sipped this first one, a middle-aged man hauling a pack much larger than mine came barrelling awkwardly through the door. He plunked himself down beside me at the bar.

I turned and offered a big smile. “Where are you from?” I asked, “Germany!” he replied, with a smile that rivaled my own.

I began to ask him questions but he stopped me mid-sentence. “Little English, very little,” he said. I nodded. There was no malice in his silencing me.

As I gathered my things to leave, I felt him tap my shoulder. “Buen Camino!” he offered.

“Buen Camino!” I replied. I would soon learn these were the two Spanish words every pilgrim was guaranteed to know. They were a happy recognition of a shared mission.

I’d set off that morning from Villafranca del Bierzo with the goal of walking the approximately 29 km to the hilltop town of O’Cebreiro. My plan was to follow the official stages of the Camino Francés: the entire path is divided into sections of between 18 and 37 kilometers. Most start and end in relatively larger towns that have at least a few accommodation options, and the actual terrain varies greatly, from muddy mountain paths to sections that follow the local highway.

As afternoon turned to early evening, I realized I had been walking for six hours and was still a good five kilometers out of O’Cebreiro. The trail had emptied of pilgrims. I crested a steep hill and rolled into the tiny farming town of Faba in search of a place to sleep.

In the old days, pilgrims slept outdoors or were offered shelter in barns, churches or homes. Today there is an “albergue”—a basic hostel—nearly every five kilometers, often staffed by volunteers.

The first place I came across was the Albergue German Confraternity de Faba, where a blonde retiree named Ellen Zierott welcomed me, collecting the five euro fee and explaining the rules: boots off in the front hall, lights out at 10 pm and everyone out by 8 am sharp.

I poked my head into the expansive dorm room lined with dozens of bunk beds, about half occupied by pilgrims in various stages of repose.

The early bedtime was rapidly approaching, so I ran down the road to one of the town’s two cafes to wolf down a plate of pasta, then returned to slip under the thin fleece blanket provided and say goodnight to an older Japanese woman tucking herself in two meters away. The lights went out and within what felt like seconds a cacophony of snoring erupted. I cursed myself for not bringing earplugs and then, exhausted, promptly fell asleep.

“Good morning!” said a perky voice. It took me a moment to realize it was Ellen.

“Good morning!” responded a chorus of groggy but cheerful voices.

I looked at my watch: 7 am. Time to start walking.

I stepped out into the dark, icy morning. The pilgrims in the cafe the evening before had spoken of snow—the climb to O’Cebreiro reached an altitude of 1,296 meters—but I had laughed them off. After all, it was April in Spain.

The wind was gentle at first, but within an hour the trees bordering the mountain path were whipping wildly to and fro. A town emerged atop the hill: O’Cebreiro. I turned into the first open door.

Inside the tavern coals glowed in the enormous fireplace. I pulled up a stool next to a grandfatherly man with blue eyes and a white beard.

“One caldo Gallego,” said the man to the barmaid. He turned to me. “It’s very good here.”

I too ordered what turned out to be a typical Galician dish—delicious pork broth with greens and white beans steaming in a rough brown bowl with hearty bread. We began to chat. He was Günter, from Germany, and this was his third time on the Camino.

There were certainly a lot of Germans on the path. I would later learn this was due in large part to a 2014 book about the Camino by a German TV celebrity.

“People have problems,” said Günter in his rough English. “They come on the Camino and the problems

go away.”

Just then the door burst open, letting in a gust of cold air and a few large snowflakes. In walked another German, as it turned out also called Günter. This one was younger and bundled in high-tech gear. He called out for his own caldo.

“I am an inventor,” he said when I asked why he was on the Camino. “Have you ever seen an inflatable movie screen? That was me.”

Günter’s invention business had been going great, when suddenly his partners swindled him out of his share. “I was devastated. I lay on the couch for a year,” he said.

One day he picked up a book his wife had been reading. It was The Pilgrimage by Brazilian writer Paulo Coelho, a personal account that had almost single-handedly reinvigorated public interest in the Camino in the 1980s. “Ten days later I was on the Camino,” said Günter. Today he was nearing the end of his sixth pilgrimage.

It was the Camino that broke his depression and that he credited with helping him finally conceive a child after years of trying. I was struck by the intensity of his story.

We finished our soups and headed out into the snow. The Günters led the way through the gathering whiteness. Soon they were distant shapes, minutes later they were gone and I found myself trudging the mountain path alone.

In the afternoon I met Hans-Peter, from Switzerland, while taking a break to sip a much needed café con leche. I was feeling burnt out but Hans was in the mood to chat.

“Cold out there?” he offered. I responded dutifully in the affirmative. My cheeks were turning scarlet and felt strangely bruised as they thawed, which I mentioned.

“Have some!” said Hans, and held out a tiny tub of Vaseline. I rubbed it all over my face.

“We walk together?” Hans asked with a smile.

My new Swiss friend seemed to bounce along. “Look, here,” he said, pointing to a large patch of smooth stone in the path. “This stone was worn down by the millions of people who walked here before us. Kings, priests, popes.” He paused. “Can you imagine an old king being carried down this very path?”

Indeed I could, with Hans as my guide as we neared our next stop, the sleepy hamlet of Triacastela.

I’d failed to break in my hiking boots before setting off and the next day, by the time I was about three hours out of Triacastela, I was finding it difficult to walk. My surroundings were breathtaking—green fields bathed in gentle sunshine—yet all I could think about was the searing pain in my Achilles tendons.

I stopped for lunch at a roadside cafe and wearily unlaced the torture devices. Fellow pilgrims listened sympathetically as I described the agony wrought by my boots. We all knew there was only one thing to be done—keep walking. Pushing through physical pain seemed almost a welcome experience here. I imagined that for pilgrims with religious motivations, pain could be seen as a sign of devotion. For me, struggling on gave me a sense of accomplishment. I laced those suckers back up and winced my way onwards.

Over the next several days, the Camino went from being my journey to my home, and I fell into a series of habits that doubled as survival tactics.

I’d start each day by waiting until nearly everyone had departed. Then I’d slowly prepare for the day in peace. My mind found a rare stillness. Life here was wonderfully simple: wake, walk, eat, sleep.

I stuck to a four-kilometer per hour walking pace. In the mornings I was usually in the mood to be alone, walking in front of or behind nearby pilgrims. In the afternoon I’d match up with someone whose life story I thought I’d like to hear.

Those stories were many. There was Andres, the tall young man who had started the Camino from the doorstep of his house in Freiberg, Germany. “I like to meet interesting people and be in beautiful nature,” he told me. “But I do also love walking. I need it,” he admitted.

There was the Finnish girl who dreamed of being a sailor, the young Romanian who’d fallen hopelessly in love on the Camino, the young Brit who had started in Seville, the elderly Chinese couple who lived in Manhattan. To my delight, the whole hodgepodge cast of characters kept popping up wherever I went: on the trail, in a cafe, in the bunk above me at an albergue.

Never had I felt so alone and yet so among friends. I carried this wonderfully odd feeling with me as I walked the final 20 kilometers to Santiago.

At last, the city came into sight, and then the cathedral, an epic Romanesque structure—which over the centuries had been added onto in Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque architectural styles—nearly 1,000 years old. As I approached, pilgrims were streaming in, embracing one another, crying, laughing, and praying.

It was over. I had done it. Yet as I received my compostela—the official certificate of completion—my elation was mixed with a profound sadness. My treasured simple routine—wake, walk, eat, sleep—was ending. I would return to a whirlwind life of tasks and distractions.

But then something occurred to me, something Andres had told me that very morning. “It’s not about the Camino,” he said. “It’s about following those little yellow arrows in your everyday life.”

I realized I could carry the Camino with me: its simplicity, inherent kindness and openness to strangers. Those “yellow arrows” were my own instincts, my own heart. They would tell me where to go.

I made myself a promise there and then that I would be back the following year to walk the Camino Francés from start to finish.

Only next time, I’ll bring a better pair of boots.